Extend the Grazing Season: Using Stockpiled Forage for Early Spring Grazing

Grazing early in the season (April and May) reduces reliance on stored feed and allows beef producers to make the most of stockpiled perennial forage resources. According to the 2025 Canadian Cow-Calf Adoption Rates and Performance Levels Report, up to 61% of Canadian producers winter cattle in pastures for all or part of the winter. For those producers not using confined feeding during this time, early-season grazing provides a transition from winter grazing or feeding to spring and summer grazing.

Early-season grazing isn’t about moving from pen to pasture; it’s about strategically managing cool-season grasses to balance nutrition, regrowth potential and pasture longevity. With the right timing, species selection and rest strategies, producers can take advantage of stockpiled forage and cool-season tame grasses to start off the grazing season before warm-season or native forages are ready.

“Every bale of hay we don’t feed is money we keep in our pocket,” says Brian Harper, who manages a cow-calf and yearling operation near Brandon, Manitoba. Besides the feed cost savings, “our cows are healthier, they’re on pasture year-round, and we haven’t had any feet or digestive issues. The exercise and consistent high-quality nutrition really pay off.”

Leah Rodvang, a cow-calf producer from east central Alberta, agrees about the economic and animal health benefits, adding, “Early-season grazing is an important management tool during May calving to reduce the risk of scours in newborn calves.”

When timed right, early-season grazing can:

- Extend the grazing season

- Reduce feed costs

- Maintain or improve pasture productivity

- Provide two grazing periods in one season

- Support calving management systems

Where and When To Include Early-Season Grazing

Rest periods are critical during early spring grazing. Because plants initiate growth during this period, grazing plans need to include adequate rest to allow for plant recovery and regrowth. Providing sufficient rest increases both above and below ground plant biomass, carbohydrates and growth rates when compared to plants grazed without a recovery period. Brian follows a rule of leaving 20% of his acres ungrazed each season to rest completely and begins grazing on this stockpiled forage the next spring. “Stockpiled forage is essential,” Brian says. For him, planning in advance and moving daily have supported grazing from when the snow melts until it is too deep to dig through.

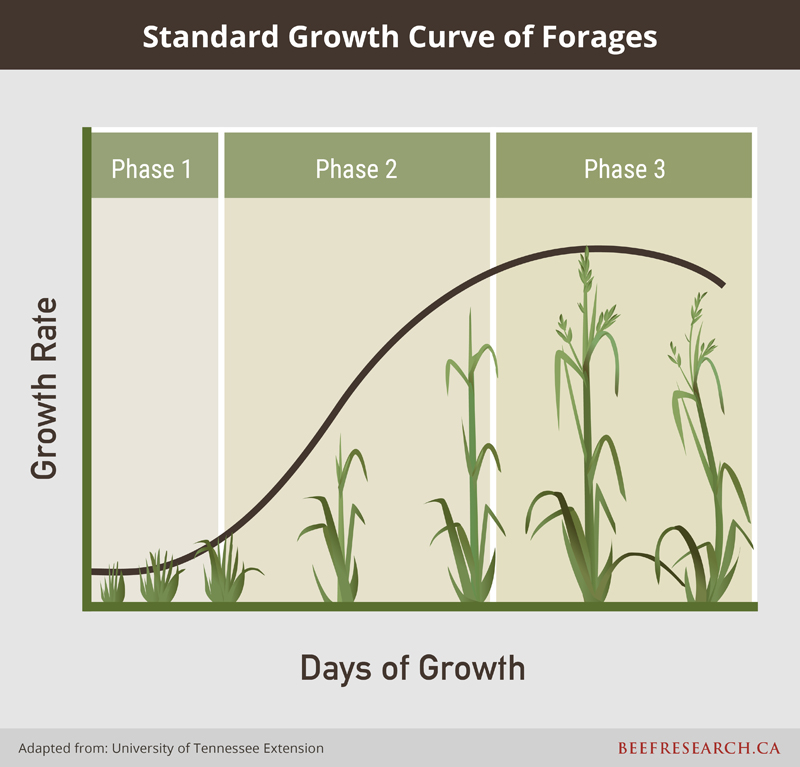

During early-season grazing, cattle remove critical leaf matter during Phase 1 of plant growth, when plants are especially vulnerable (Figure 1). At this point, the plant is relying heavily on root resources for growth and removing leaves during grazing reduces the leaf area available for photosynthesis. Managing grazing for lower plant utilization leaves more leaf area to photosynthesize and puts less stress on the plant roots. Extended rest periods provide additional time for the plants to both grow above ground and return nutrients to the roots. Without rest, desirable grazing plants lose their competitive advantage, leading to encroachment of undesirable or invasive plant species.

Producers can utilize a skim grazing strategy, moving cattle through the pasture system at a very rapid rate with a utilization rate lower than 50%. This allows only the very tips of the leaves to be defoliated, enabling the plant to continue photosynthesis with the remaining parts of the leaves. The rate at which producers will have to move from pasture to pasture will depend on the size of their pastures and herd, ranging from a few hours to a few days. “During early-season grazing, we rely on stockpiled forages from previous seasons. However, once the grass starts growing, we want to manage carefully to ensure that the grasses have enough leaf to continue photosynthesizing,” Leah says. “Estimating a 50% forage utilization is a comfortable management strategy for us.”

Brian also relies on stockpiled forage for early-season grazing. However, his grazing system looks different. Grazing acres are split into thirds: the grazing season acres, the buffer zone and stockpile. “We graze as much as 80%, but we balance that off with a longer rest period. Rainfall and timing of grazing impact the length of the rest period.” During the growing season, the grazing season acres are grazed multiple times. If the grazing season acres are not sufficient, cattle move to the buffer zone acres to allow rest and recovery before returning to the grazing season acres when plants are in Phase 2 (Figure 1). The stockpile section is given a full season of rest and used for early spring grazing, before and during spring growth.

How To Plan for Early-Season Grazing

“Planning is critical,” says Leah. Early-season grazing depends on stockpiled forages and requires planning during the prior growing season to ensure adequate forage availability. Depending on regional weather conditions, pastures may be grazed the previous season and left with time to regrow prior to winter, or the pasture may require an entire season of rest.

Regardless of location or system, a key principle of grazing management is to rotate the timing of pasture use each year. Begin the grazing season in a different pasture each spring and vary the schedule annually across paddocks. Develop and follow a grazing plan to ensure pastures are used within their capacity for recovery.

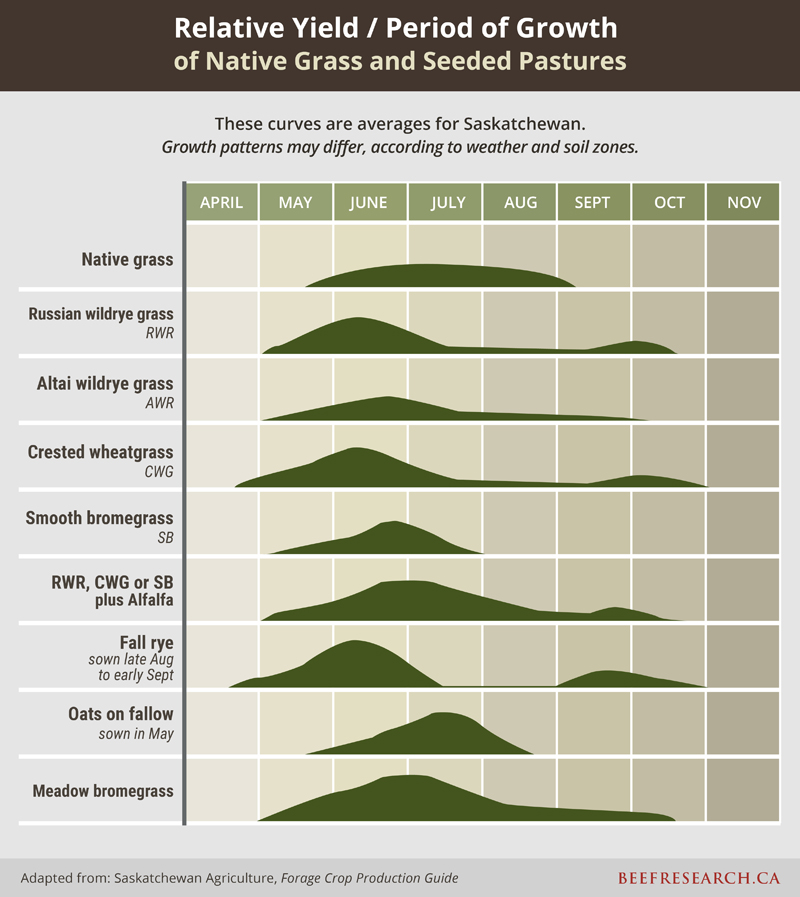

Choose pastures for early-season grazing based on location and species type. Locations with high, dry points and harder soils are ideal, as grazing these first will reduce cattle damage to plants and soil. Use tame pasture with early growing plants for April and May grazing. “On our ranch, the primary tame forage is crested wheatgrass,” says Leah. “The earlier we can use these pastures, the better, as crested wheatgrass is less attractive to the cows after mid-July. This also leaves our native pastures for later-season grazing.” Crested wheatgrass, a tame forage, begins growing early in the year and can maintain growth after early grazing (Figure 2).

Depending on the level of stockpiled forage, supplemental protein, energy, minerals or vitamins may be needed to ensure cattle nutritional requirements are met.

“We use second-cut alfalfa hay to boost protein so the cows can use up the fibre from the stockpile,” Brian explains. “Once the grass comes on strong, they transition to just grazing.”

How and when supplementation is provided may also affect how pastures are rotated for grazing, another important part of the planning process. Sample standing forage and send for a feed test evaluation to ensure your cattle’s nutritional needs are met. If using early-season grazing as part of your calving management strategy, your cows are at the point in their production cycle with the highest nutrient requirements. Stockpiled forage without supplementation will not provide adequate nutrition.

Throughout the early grazing period, monitor cattle, pastures and new growth and adjust your plan as needed. Cattle condition should be evaluated as an indicator that cattle are receiving adequate nutrients. Monitor when grass begins to grow in addition to the stockpiled forage. When early-season grazing is finished and cattle are moved to pastures with little or no stockpiled forage, ensure grasses in these pastures are at the three-leaf stage of growth or later.

For producers wanting to try early grazing, Leah recommends starting with just one pasture.

“Test it on a field you can watch closely, rotate quickly and make sure you have good water access.” She advises. “It’s about learning how much to take, how fast to move and how much to leave behind for regrowth.”

Continue to monitor these pastures throughout the remainder of the grazing season to assess pasture recovery and regrowth. These observations can be used to plan for the upcoming year.

Final Thoughts

Early-season grazing offers significant advantages when managed carefully. By understanding the growth patterns and rest needs of cool-season grasses, cattle producers can reduce feed costs, maintain pasture productivity and set the stage for a successful grazing season. While grasses are tough, they thrive with rest. Timing, species choice and rotation are the building blocks for productive, sustainable early grazing systems.

- References

- Manitoba Agriculture. Manage early spring grazing.

- Kowalenko, B., Romo, J.T. 1998. Regrowth and rest requirements of northern wheatgrass following defoliation. Journal of Range Management, 51 (1) 73-78.

- Romo, J.T., Harrison, T. 1999. Regrowth of crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum [L.] Gaertn.) following defoliation. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 79, 557-563.

- McCartney, D. 2011. To Rest or Not Rest, That’s the Question! Canadian Cattleman.

Sharing or reprinting BCRC posts is welcome and encouraged. Please credit the Beef Cattle Research Council, provide the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you have chosen to share the article by emailing us at [email protected].

The BCRC is funded by a portion of the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off.

Your questions, comments and suggestions are welcome. Contact us directly or spark a public discussion by posting your thoughts below.