A cow should have a calf every year. While that is a straightforward and simple statement, beef cattle producers know it takes effort, planning and management to make this happen. One way to achieve this goal is to establish well-defined breeding and calving seasons.

| Key Points |

|---|

| A controlled calving season is a 60-90-day period in which all calves are born. |

| A controlled calving period allows improved nutrient, health and marketing management due to animal similarity throughout the year. |

| Research has found that year-round calving results in lower returns to producers relative to spring and fall calving. |

| A shorter breeding season may require adjusting the bull-to-cow ratio. |

| Year-round marketing provides risk management as only a portion of the calf crop is sold at the annual low or high. |

| For those planning to shorten their calving season or shift to an earlier or later period, a slow adjustment is recommended to avoid negatively impacting conception rates. |

Calving Seasons Across Canada

The key measures of success and the approach to improving herd reproductive performance will vary depending on the calving system. Cow-calf operators across Canada implement a range of calving seasons, including:

- Winter (early January through March),

- Spring (March through May),

- Summer (June to early August),

- Fall (September to early November), and

- Year-round (no defined calving period).

The 2022/2023 Canadian Cow-Calf Survey reported that the average breeding season length for cows and heifers was 93 days, and the average calving season length was 74 days. It was noted that some operations have year-long breeding and calving seasons.

Selecting a Calving Season

A controlled (or defined) calving season is a 60- to 90-day period in which all calves are born. A defined calving season (spring or fall) has been shown to1:

- improve the uniformity of cattle for marketing,

- provide shorter time between calving to allow cows to have a calf every 12 months,

- reduce labour requirements at specific times of the year, which allows the farmer to focus on alternative enterprises such as crop and forage production,

- improve weaning weights – calves born in the first 21 days of the calving season are often the heaviest at weaning, and tend to have better carcass quality2

- help producers more accurately time cow vaccinations, such as a scours prevention vaccine, which needs to be given at a specific interval before calving, and

- reduce the variation in nutritional requirements within the herd at any one point in time.

All of this could help beef cattle producers save money on herd inputs.

Video: How to Increase Profit by Improving Calving Distribution

To assess your herd’s current calving distribution and evaluate the impact of moving to a more condensed calving season, learn more about and try the Value of Calving Distribution Tool.

Overall, a controlled calving period allows improved nutrient, health (i.e., vaccination program) and marketing management due to uniformity or animal similarity throughout the year. Regardless of the time of year chosen, a controlled calving season provides clear time periods for when things happen on the farm.

Selecting a defined timing of calving (i.e., winter, spring, summer or fall) allows producers to employ strategic management as the herd moves through the production cycle as a unit. This takes the form of matching herd genetics to the environment as well as improved feed management efficiency by planning to provide forages of the highest quality when the cow herd has the highest nutrient demands (after calving and through the breeding season). However, in many cases, there are additional considerations, such as other demands on labour that need to be accounted for, make sure you account for these things and that your operation is capable of handling it before switching over. Find the season that works best for your farm.

Read the BCRC’s post — One Size Doesn’t Fit All — for learnings from the Canadian Cow-Calf Cost of Production Network’s future farm scenario, simulating the potential costs and revenues of tightening the calving season over a five-year period.

Year-round calving or long calving seasons (five months or more) requires less active management, typically at the expense of increased calving intervals (time between calving). Research has found that year-round calving reduced returns to producers relative to spring and fall calving.3 It was hypothesized however, that small-sized operations sacrificed returns to calving-season control for ease of management and the ability to avoid investment in facilities to separate herd sires from the remaining breeding stock.

For small herds considering transitioning to a defined calving season, the logistics of managing a bull can represent a significant barrier. The goal is to keep bulls in a separate and secure pasture or holding area to avoid unintentional breedings, without caring for them becoming too challenging. One option is to share bulls with other producers so they are only on the premises at the designated breeding time. This may be appealing if several neighbours are switching to a defined calving season and may assist in having an adequate number of bulls to breed the herd in the designated breeding period. Another option is the use of artificial insemination (AI). There are many benefits to using AI, including greater calf crop uniformity, reduced disease transmission, a shorter calving season with synchronization, reduced heifer injury, lower bull maintenance costs, increased handler safety and enabling top sires to produce more offspring per year than would be possible naturally.

A shorter breeding season may require increasing the bull-to-cow ratio (note that the ideal bull-to-cow ratio will vary depending upon multiple factors including pasture size and conditions as well as concentration of the herd.) Sharing bulls could make that feasible while addressing the question of where to keep bulls when not breeding. However, there are biosecurity considerations that should be discussed before bulls are shared between operations.

If year-round marketing is utilized, weaning weights might not suffer, and it allows producers to capitalize on the seasonality of the market. Adjusting to a more seasonal cash flow can represent challenges if an operation is used to year-round marketing. Year-round marketing also provides risk management, as only a portion of the calf crop is sold at the annual low or high.

Dual calving systems, such as part of the herd spring calving and the other part fall calving, allows producers to have options for more dynamic management practices. For example, late calvers or open cows from one group can be shifted to the next. However, good records are needed to ensure cows are not continually shifted between groups. Having a system where late-calving cows can be shifted from a spring group to a fall group, but never vice-versa, can avoid that. This splits the labour requirements with fewer cows calving at a time. It also means calving seasons can be chosen to avoid weather issues such as mud.

Sandhills Calving System

For some producers, adopting the Sandhills Calving System has improved herd health and time management at a busy time of year. Named by a University of Nebraska professor who developed the idea, some refer to it as “leave behind calving,” the “drop-back method” or “strategic calving management.”

The Sandhills System involves moving pregnant cows to different “clean” ground while leaving freshly calved pairs in the field they were born in. This method helps minimize direct contact between older calves and younger calves, while reducing the transfer of viruses and the build-up of disease-causing pathogens in the calving area. Regardless of what producers call it, moving pregnant cows to calve on clean ground and leaving freshly calved pairs remaining in their pasture is a practical way to improve health and reduce scours at calving.

Read “How Fresh Pens and Pastures Prevent Calf Losses” to discover how different producers have made new calving systems work for them.

Moving pregnant cows to fresh ground and leaving pairs behind can limit calf sickness.

Foothills Calving System

Dr. Elizabeth Homerosky has worked to develop a modified Sandhills Calving System with producers who prefer to keep the calving herd close to corrals and calving facilities and move the cow-calf pairs to new ground. These may be smaller beef operations, purebred producers or farms with a smaller land base.

In this system, the bred cow herd is held in one pasture or calving area and, as soon as calves are born, cow-calf pairs are moved to the next area or nursery pasture.

Homerosky recommends cow-calf pairs be moved away from the main pregnant cow herd within 24 hours of calves being born. For example, if 10 calves are born today, as soon as they have nursed and are ambulatory, move that group to the new paddock or first nursery pasture within 24 hours. If 10 calves are born tomorrow, do the same thing — move those pairs into the paddock or nursery pasture to join up with the first day’s calves. Ideally, she recommends following this approach for about 10 days (no more than two weeks).

Keep moving cow-and-newborn-calf pairs into that first nursery pasture for 10 days to two weeks (or before if the pasture reaches capacity). At the 10-day or two-week mark, start moving cows and newborn calf pairs to fresh ground in a new second nursery pasture and continue using it for 10 to 14 days before starting a third nursery pasture.

“Newborn calves do not shed any scours pathogens in their manure within the first 24 hours of life, so that’s why it is important to move those calves within 24 hours,” says Homerosky. Moving the pairs limits their exposure to any pathogens that may be present around the main cow herd, and they are also not adding to the pathogen load in the calving area.

If a case of scours does develop, the Foothills Calving System allows a producer to contain or manage the outbreak to within a small group of animals, rather than the whole herd.

How to Transition Calving Seasons

For those planning to shorten their calving season or shift to an earlier or later time period, a slow adjustment is recommended to avoid negatively impacting conception rates. When shifting to an earlier calving season, producers may consider breeding first-calf heifers earlier than mature cows to allow a longer time to rebreed while also maintaining the desired calving season. However, this may require exposing more animals at a younger age to get the necessary conception rate.

Another option is to use hormone protocols to ensure heifers are bred earlier than cows or at the very beginning of the designated calving season. If you are looking to maintain a calving interval of fewer than 60 days, you don’t want heifers calving before the rest of the herd, but you can make sure they are at the very beginning of the calving period. In this situation, ensure heifers are adequately developed at the time of breeding and are bred to a calving-ease bull since they will be bred at just over a year old in most cases.

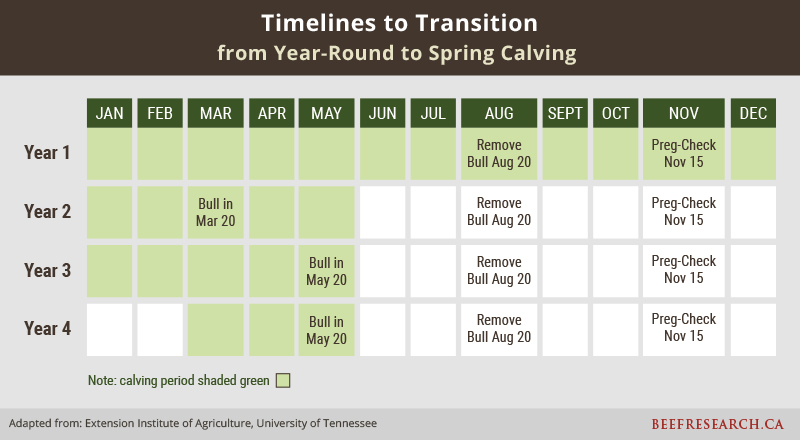

The most widely used procedure for converting from year-round calving to a defined calving season is to convert slowly over a three-year period (see table below), targeting the period when the majority of cows are already calving within the year-round cycle. This method usually results in a transition that does not require culling many cows in one year and is more economically feasible than transitioning in a single season. For some situations with high purchasing costs for bred heifers or raising replacements, an even slower transition might be deemed a better option.

If there are enough cows to run dual calving seasons, grouping based on initial pregnancy status can make the transition less costly. As mentioned above, doing this will create an opportunity to shift open cows to the other breeding season when they come open for the first time, provided there are no other reasons for culling (e.g., poor calf performance, udder/mastitis, lameness).

To read first-hand experiences of producers who did their homework and planned ahead before shifting calving seasons, visit the BCRC post “Calving Season Timing and Transition.”

- References

-

1. Carpenter, B. and L.R. Sprott. Long Calving Seasons: Problems and Solutions. AgriLife Extension, Texas A&M System. B-1443. 6/07. Available here.

2. Funston, R. N., Musgrave, J. A., Meyer, T. L., and Larson, D. M. (2012). Effect of calving distribution on beef cattle progeny performance.” J. Anim. Sci. 90:5118-5121.

3. Doye, D., M. Popp, and C. West. (2008). Controlled versus Continuous Calving Seasons in the South: What’s at Stake? Journal of the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers. 90:60–73.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Brenna Grant, Manager, Canfax Research Services, for contributing her time and expertise in writing this page.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us.

This content was last reviewed June 2025.