Cracking the Heritability Code — Choosing Traits That Pay Off

Improving the genetics of your beef herd starts with knowing which traits you can change through genetics and which traits respond better to management practices. Because cattle have a long generation interval, every bull or replacement heifer you choose affects your herd for years. That’s why understanding heritability — and how traits interact with each other — helps ensure your breeding decisions move your herd toward your production goals.

What Heritability Really Means

Heritability tells us how much of a trait is controlled by genetics versus the environment and/or management. It’s expressed as a number between zero and one:1,3

- High heritability (over 0.40): Traits are strongly influenced by genetics, meaning you can make changes more quickly by selecting the right replacements and bulls.

Examples: ribeye area, marbling, weight and growth traits. - Moderate heritability (0.15 to 0.40): Traits that can be improved through both genetics and management.

Examples: milk production and calving ease. - Low heritability (less than 0.15): Traits are mainly influenced by crossbreeding (e.g., heterosis/hybrid vigour and management (e.g., nutrition, colostrum, vaccination).

Examples: fertility, reproductive efficiency and disease resistance.

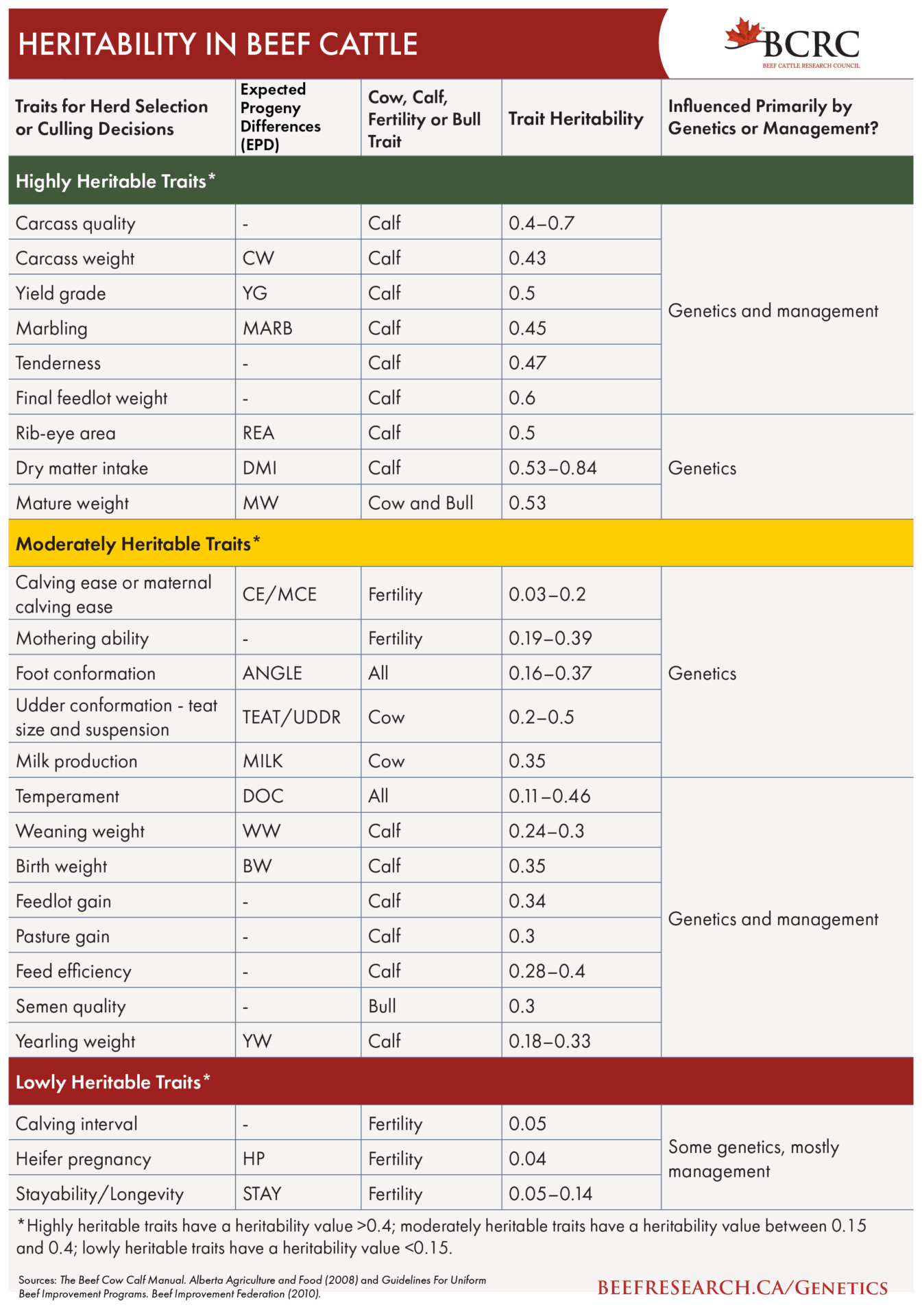

Weaning weight has a heritability of 0.24 to 0.30, which means that 24% to 30% of the differences we see in weaning weights between cattle in a herd are caused by genetics. Table 1 provides a summary of the heritability of common traits. The higher the heritability, the more progress you’ll make through selection. Traits with low heritability still matter — they just require dedicated management to go along with genetic decisions.

As an example, improving pregnancy rates in beef cattle cannot be achieved through genetics alone. This is primarily due to fertility traits having low heritability and being heavily influenced by management factors such as nutrition, body condition, health and breeding season management. Until those areas are optimized, selecting new genetics alone won’t move the needle.

In contrast, calving ease is moderately heritable, and information can be used strategically when planning a heifer breeding program. Selecting sires with high calving-ease genetics can help avoid calving difficulties.

Table 1. Heritability in beef cattle

Trait Correlations: When Changing One Trait Affects Another

Traits don’t work in isolation. Selection for one trait can cause an increase or decrease in the expression of another, sometimes in ways you don’t want. Trait correlations are expressed as a number between +1 and –1.

A positive (+) genetic correlation means that as one trait increases, the other also tends to increase. A negative (-) correlation means that as one trait increases, the other tends to decline. Despite the positive/negative labels, neither automatically indicates whether the relationship is beneficial. A correlation is considered favorable when selection for one trait leads to a desirable change in another2. Table 2 shows examples of some trait correlations.

Table 2. Genetic correlations between selected traits1,2,4

| Trait 1 | Trait 2 | Correlation* | Strength | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | Calving Interval | Positive | High | Cows that produce more milk may take longer to rebreed due to higher energy requirements. |

| Milk | Total Energy Intake | Positive | Moderate | Higher-milking cows usually require more feed to maintain body condition. |

| Calving Ease Direct | Maternal Calving Ease | Negative | Low to Moderate | Improving calving ease direct of an animal itself can slightly reduce a daughter’s calving ease. |

| Fertility | Leanness | Negative | Moderate-High | Fast growing, lean genetics become larger cows that can have difficulty maintaining body condition and rebreeding. |

| Yearling Weight | Mature Cow Size | Positive | Moderate-High | Selecting for faster growing and larger calves often increases mature cow size. |

| Milk | Weaning Weight | Positive | Moderate | Higher milk production typically results in a higher calf weaning weight. |

| Birth Weight | Mature Weight | Positive | High | Smaller calves generally grow into small cows and bigger calves often become big cows. |

| Yearling Weight | Carcass Weight | Positive | High | Selecting for yearling weight will usually increase carcass weight. |

| Yearling Weight | Marbling | Negative | Low-Moderate | Selecting for yearling weight may decrease marbling slightly. |

| Yearling Weight | Ribeye Area | Positive | Moderate | Selecting for yearling weight tends to increase ribeye area. |

*A positive (+) genetic correlation means that as one trait increases, the other also tends to increase.A negative (-) correlation means that as one trait increases, the other tends to decline.

Understanding these relationships helps avoid unintended consequences. For example, weight and growth traits tend to be positively correlated. So, selecting heavily for low birth weights will ultimately lead to smaller heifers that may be more prone to calving difficulties or calves that don’t grow as well as desired. Similarly, selecting large weaning or yearling weights will eventually produce bigger mature cows that cost more to feed.

These relationships mean that selection decisions should be made with your operation’s goals in mind. A herd keeping replacement heifers may prioritize balanced growth and moderate mature size, while a cow-calf operation selling all calves at weaning may put more emphasis on growth and weaning weights because they aren’t keeping replacements.

Key Questions to Ask When Managing Trait Selection:

- Is this trait something I can improve through genetics (e.g., growth, carcass traits), or would crossbreeding and/or management be a more effective strategy (e.g., fertility, health traits)?

- Will improving this trait support my overall goals (e.g., fertility, feed efficiency, carcass quality)?

- What traits need to be balanced so I don’t create problems elsewhere (e.g., heavy calf weaning weights often lead to large mature cows)?

Use of Selection Indexes to Make Balanced Progress

Selection indexes help simplify genetic decisions by combining several traits into one value that reflects your breeding goals while also accounting for trait correlations behind the scenes, making it easier to avoid unintended trade-offs and helping prevent single-trait selection. Think of a selection index like a financial index: instead of tracking every single trait (or “stock”) on its own, the index combines them into one value based on their economic importance.

Like expected progeny differences (EPDs), indexes are breed-specific, so they cannot be compared across breeds, unless the genetic evaluation contains information from several breeds. Knowing which indexes fit your operation can make bull buying simpler and more profitable.

While indexes are extremely useful, they should be used alongside visual appraisal, structural soundness and good management to make the most informed selection decisions.

Examples of selection indexes include:

- All-Purpose Indexes

- Best for herds where heifers are kept and steers are marketed from the same calf crop

- Balanced across maternal and terminal traits

- Examples: Canadian Angus Association’s Canadian Balanced Index (CBI), Canadian Simmental All Purpose Index (API)

- Best for herds where heifers are kept and steers are marketed from the same calf crop

- Balanced across maternal and terminal traits

- Examples: Canadian Angus Association’s Canadian Balanced Index (CBI), Canadian Simmental All Purpose Index (API)

- Maternal Indexes

- Designed to build better mother cows

- Prioritizes fertility, milk and stayability

- Example: Canadian Hereford Association’s Maternal Productivity Index

- Terminal Indexes

- Used when all calves are sold and none kept for replacements

- Focused on growth, feed efficiency and carcass traits like marbling and ribeye area

- Example: Canadian Charolais Association’s Terminal Sire Index

Building a more productive herd starts with understanding which traits are driven by genetics and which ones respond more to management. Knowing the heritability of key traits and how those traits interact helps ensure that breeding decisions move your herd in the right direction without creating unwanted challenges.

- References

- Rolf, M. (2015). Genetic Correlations and Antagonisms.

- Beef Improvement Federation. (2010). Guidelines for Uniform Beef Improvement Programs.

- Koots, K. R., Gibson, J. P., Smith, C., and Wilton, J. W. (1994). Analyses of Published Genetic Parameter Estimates for Beef Production Traits – Heritability. Anim. Breed. 62: 309-338 (Abstr.).

- Koots, K. R., Gibson, J. P., and Wilton, J. W. (1994). Analyses of Published Genetic Parameter Estimates for Beef Production Traits – Phenotypic and Genetic Correlations. Anim. Breed. 62: 825-853 (Abstr.).

Additional Resources

- Canadian Beef Improvement Network Dashboard

- AgSights: Bull and Replacement Heifer Genetic Evaluations

acknowledgements

Thanks to the following individuals for contributing their time and expertise to review this article and related resources:

- Karin Schmid, Beef Production and Extension Lead, Alberta Beef Producers

- Chelsey Siemens, Livestock and Forage Extension Specialist, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture

- Macy Liebreich, Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Beef Breeds Council

- Stephanie Lam, Director of Research, Livestock Research Innovation Corporation

Sharing or reprinting BCRC posts is welcome and encouraged. Please credit the Beef Cattle Research Council, provide the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you have chosen to share the article by emailing us at [email protected].

The BCRC is funded by a portion of the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off.

Your questions, comments and suggestions are welcome. Contact us directly or spark a public discussion by posting your thoughts below.