Calf 911 - How to Spot Dehydration in Young or Scouring Calves ▶️🎙️

CLICK THE PLAY BUTTON TO LISTEN TO THIS POST:

Listen to more episodes on BeefResearch.ca, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music or Podbean.

It’s a great feeling when a calf arrives on the ground safe and sound. Ideally, things go well, and cows and newborn calves thrive. However, it’s important for producers to take the time to look for signs of early illness in neonatal calves. Being able to recognize the symptoms of disease and dehydration in baby calves is a simple and effective practice that can make a big mark on your bottom line.

Calves with scours are at a high risk for dehydration and hypothermia. When calves infected with neonatal scours die, it is ultimately because of dehydration, not the pathogens that cause the disease. Having practices in place on your operation to identify, manage and rehydrate calves suffering from scours or other causes of dehydration can increase the chance of recovery and optimize the health and wellbeing of young calves.

Here are some steps producers can use to evaluate the dehydration and health status of young calves:

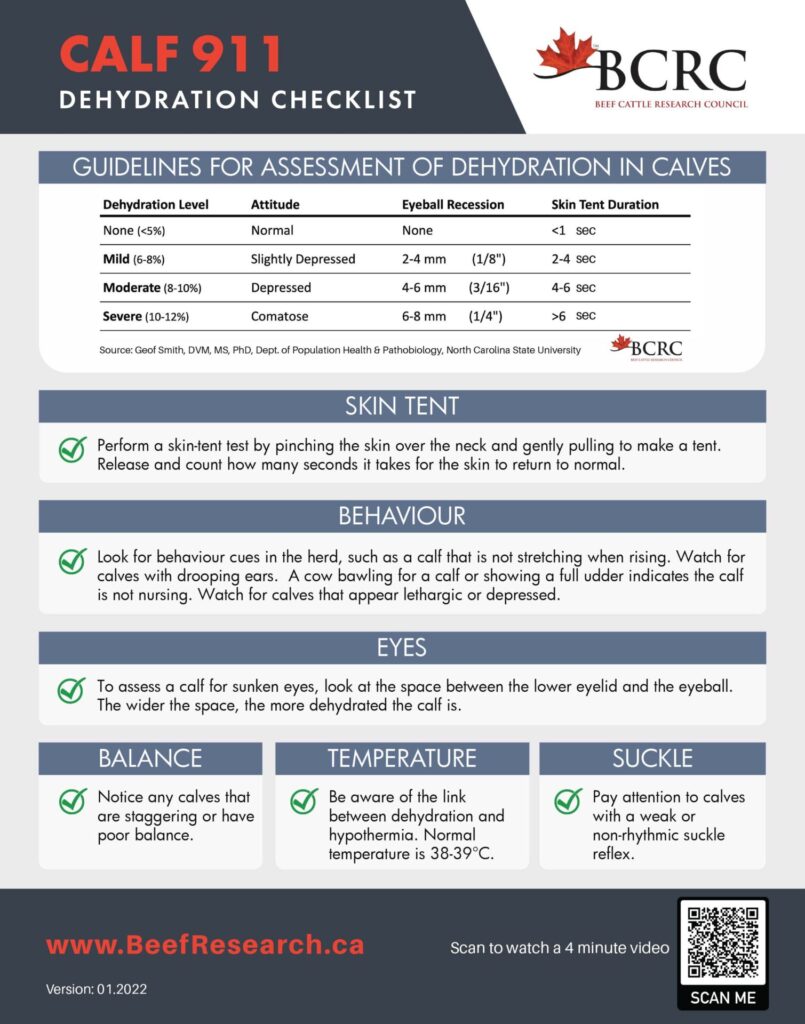

- Perform a skin-tent test by pinching the skin over the neck and pulling gently to make a tent, then count how many seconds it takes for the skin to return to normal.

- Look for behavior cues in the herd, such as a calf that is not stretching when rising or a cow bawling for a calf or showing a full udder, indicating the calf is not nursing.

- Watch for calves with drooping ears.

- Be aware of the link between dehydration and hypothermia or cold exposure;

- Look for sunken or recessed eyes.

- Watch for depression or lethargy in calves.

- Be on the lookout for calves that stagger or have poor balance.

- Pay attention to calves with weak or unrhythmic suckle reflex.

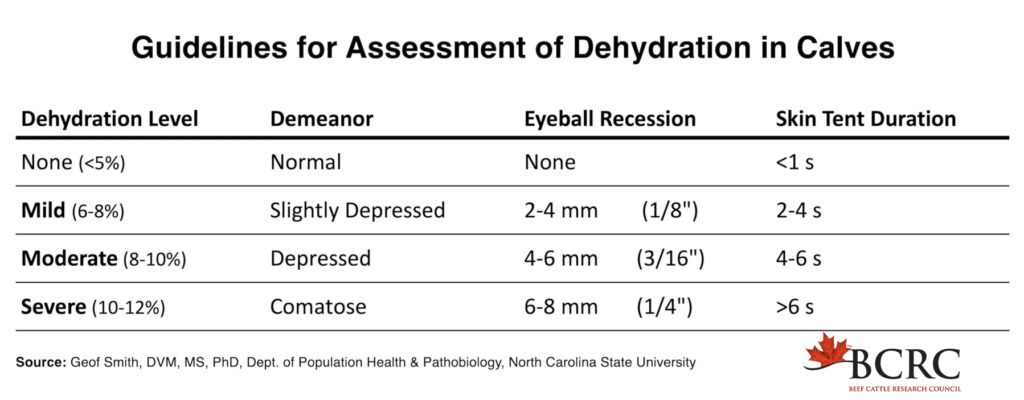

There are three degrees of dehydration: mild, moderate and severe. In some cases, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and acidosis may be occurring at once.

The treatment for a dehydrated calf will depend on the severity of dehydration and other variables. Typically, this will be done with oral fluids and an electrolyte solution. Severe cases may call for intravenous (IV) fluids and potentially sodium bicarbonate (delivered through IV or orally depending on the severity of acidosis). Fluids should be given continuously until scouring stops. Even for healthy-looking calves, there is still a risk for dehydration if diarrhea persists.

According to veterinarian Elizabeth Homerosky, DVM, of Veterinary Agri-Health Services Ltd. in Rocky View County, Alberta, there are many things to consider while evaluating dehydration. Having the ability to accurately classify the level of dehydration is key to communicating with your veterinarian and developing a successful treatment plan:

- Early intervention is key!

- An in-field test called the “skin tent” can be used to evaluate dehydration. In healthy calves, the skin will return to normal in two seconds. Anything longer is a sign that the calf is dehydrated and should be treated with electrolytes.

- A calf will appear normal until they are about 6% dehydrated.

- When calves are mildly dehydrated, symptoms such as sunken eyes and a skin-tent test of two to four seconds will occur. These calves will still have a suckle reflex, which can be tested by placing two fingers in a calf’s mouth to see if they will suck. Mild dehydration can be treated with oral fluids such as an electrolyte solution and have a high likelihood of a full recovery.

- Calves coping with moderate dehydration will spend a lot of time lying down, will not stretch when forced to rise, have a prolonged skin tent test (four to six seconds) and sunken eyes. These calves need to have oral fluids frequently throughout the day, until all symptoms are resolved, and need to be monitored closely.

- Calves with severe dehydration will have a skin-tent test that lasts six or more seconds. These calves will be unable to stand, have extremely sunken eyes and will require IV fluids with the help of a veterinarian. These calves, if they recover, will be more likely to have health problems such as pneumonia, reoccurring scours and other problems in the future.

- Most electrolyte solutions are designed to replace the electrolytes that are rapidly leaving the calf’s body due to diarrhea. Be sure to select a product that contains sodium chloride or salt (NaCl), Potassium (K), an energy source like glucose and amino acids like glycine or alanine. Other ingredients may include acetate or propionate to help the calf retain sodium and water, correct electrolyte imbalances and potentially prevent acidosis. Work with your veterinarian to choose an electrolyte product that will work for you.

- It is important to alternate feeding fluids and milk throughout the day because electrolyte powders don’t provide the energy that milk does. Milk can come from the dam or from a milk replacer product.

- Always keep separate bottles and tube feeders for scouring calves and healthy calves requiring colostrum. Be sure to clean and disinfect all feeding equipment after each use.

- Dehydrated calves have decreased blood volume and flow, which limits oxygen’s ability to circulate through the body and makes them very susceptible to hypothermia. Monitor this by taking the rectal temperature frequently and provide an alternate source of heat (i.e., hot box and warm fluids) if they are unable to maintain adequate body temperature.

- 35-38°C (95-100.4°F) is borderline hypothermia, and anything below 35°C (95°F) is considered severe hypothermia. Severe hypothermia WILL NOT be remedied by placing the calf in a hot box alone; you must gradually warm them from the inside out through feeding warm fluids. When dealing with severe cases, it is important to involve your veterinarian.

- Any time you are dealing with a scours outbreak, it is important to be in contact with your veterinarian. They are the best source of information on specific treatments and how to prevent further incidence of disease through nutrition, strategic calving management, herd vaccination and other disease mitigation strategies.

Scours is a reality on farm and dehydration is a constant risk for calves suffering from it. Having the skills to quickly identify dehydration and knowing methods for early intervention can have a meaningful reduction in the rate of calf illness and death on your farm.

For more information, visit our Calving and Calf Management webpage.

This post is part of our #Calf911 series. Read more in the series or watch more videos.

Click here to subscribe to the BCRC Blog and receive email notifications when new content is posted.

The sharing or reprinting of BCRC Blog articles is welcome and encouraged. Please provide acknowledgement to the Beef Cattle Research Council, list the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you chose to share the article by emailing us at [email protected].

We welcome your questions, comments and suggestions. Contact us directly or generate public discussion by posting your thoughts below.