Weed and Brush Control in Pastures

Healthy and productive pastures are the foundation of a successful and sustainable beef cattle operation. When weeds and brush spread into hay fields, rangelands and pastures, desirable forage species are replaced, reducing productivity and profitability.

Pastures can be impacted by annual, biennial and perennial weeds, and each region across Canada will have different weeds that are problematic.

Weeds can be introduced through many ways including:

- purchasing feed such as baled hay, greenfeed, or straw that contains weed seeds

- seed distribution by wind (e.g., kochia or baby’s breath)

- flooding that carries seeds onto a pasture (e.g. red bartsia)

- in contaminated soil or gravel

- animals returning from weed-infested pastures that bring back weed seeds in their manure.

While some weeds reduce pasture yield, others are poisonous and present a health risk to livestock. Providing cattle access to healthy, vigorous pastures reduces risk of poisoning, as cattle will usually avoid poisonous plants if adequate forage is available. Examples of toxic plants found in Canada include lupines, death camas, red maple or oak, larkspur, locoweed, henbane, water hemlock and poison hemlock.

Weed management, which includes cultural, mechanical, chemical, and biological methods, must be applied and evaluated over an extended period of time to be successful. A good weed management plan starts with cultural methods and integrates two or more additional control measures into a complete management system. The system must be applied and evaluated over an extended period of time to be successful.

Classical biological control uses natural enemies of weeds, such as insects or disease organisms. Biological control may also include the use of sheep, cattle, goats, or other large herbivores to manage weeds. While biological control is not intended to eradicate target weeds, it can be an environmentally safe, cost effective way to reduce weed pressures.

Targeted browsing of weeds by goats or sheep has been used with some success in larger areas of infestation where herbicide control is not practical. While cattle tend to avoid leafy spurge and thistle, targeted grazing as part of an integrated management plan can reduce weed density. Goats and sheep will also graze undesirable plants such as thistle, absinthe, buckbrush and aspen suckers. Fencing, herding, and predator control are required to keep goats and sheep grazing targeted areas, and safe from predators such as coyotes.

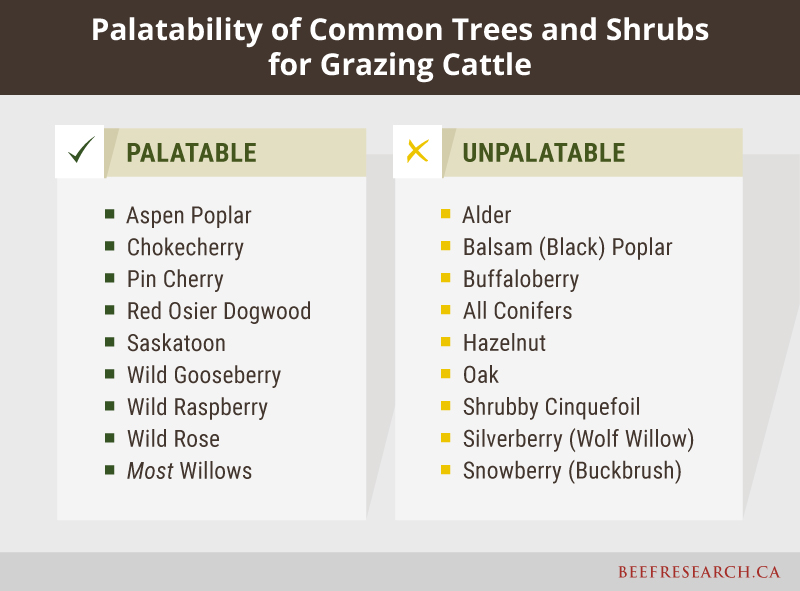

Bushes, forbs and shrubs provide habitat for wildlife, and can make up over 20% of livestock’s diet on rangelands, as cattle graze the desirable forbs and forage plants. Undesirable or invasive brush can impact wildlife habitat when encroachment alters native ecosystems. Proper identification is important to ensure that desirable plants are not targeted for weed and brush control.

In many areas of Canada, brush encroachment by trees such as trembling aspen, willow, and shrubs such as buffaloberry, hazelnut, and snowberry, reduces forage yields and availability to cattle. When determining methods to control or reduce brush, consider the cost of control relative to the increased forage production gained. Since production improvements will vary greatly from one operation to another a helpful tip is to create a budget to estimate costs of brush removal versus the anticipated gains of increased forage yield and grazing days.

To learn more about weed and brush control on pastures, visit our new webpage.

Click here to subscribe to the BCRC Blog and receive email notifications when new content is posted.

The sharing or reprinting of BCRC Blog articles is welcome and encouraged. Please provide acknowledgement to the Beef Cattle Research Council, list the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you chose to share the article by emailing us at [email protected].

We welcome your questions, comments and suggestions. Contact us directly or generate public discussion by posting your thoughts below.