Mycotoxins are poisonous chemical compounds produced by certain fungi that can contaminate cattle feed.

Mycotoxins and Beef Cattle

Often a hidden hazard in beef cattle diets, mycotoxins are a group of harmful toxins produced by certain types of fungi including mould. They can create a variety of problems for beef cattle including impaired health and reduced productivity.

It is important for beef producers to understand the threat represented by mycotoxins and to adopt appropriate prevention measures. By working to minimize risk producers can safeguard the health of their animals and ensure productivity is not derailed. Everyone doing their part can reduce the risk for Canada’s beef industry, helping to uphold high standards of quality, safety, animal care and animal health.

This page provides an overview of what mycotoxins are, the threat they represent for Canadian beef production and how to implement best practices to protect beef cattle.

| Key Points |

|---|

| Mycotoxins are poisonous chemical compounds produced by certain fungi which can create a variety of problems for beef cattle including reduced health and productivity. |

| Mycotoxins are a “hidden hazard” and only detectable with lab testing. |

| The most common causes of mycotoxin issues in Canada are fungal diseases such as fusarium and ergot. |

| The source of mycotoxins are fungi, including mould, that can be present in green pastures, cereal swaths, standing corn for winter grazing, cured and ensiled grass, cereal forages, crop co-products (straw, distillers grains, grain screenings, oilseed meals) and commercial feeds. |

| The risk of mycotoxin contamination of feed is influenced by growing, harvesting and storage conditions. |

| – Risk of Fusarium production is increased with the presence of warm, moist conditions during the flowering stage. |

| – Ergot favours cool, moist conditions during flowering. |

| The symptoms of mycotoxin toxicity will be variable depending on the toxins present, amount ingested, duration of exposure, animal condition and stage of production. |

| Symptoms of possible mycotoxin poisoning in cattle are listed below: |

| – animals consume less feed; a feed reduction greater than 30% should be investigated |

| – a decrease in growth or performance, or a failure to thrive |

| – animal seems to be frequently sick, which may indicate immune suppression |

| – animal does not respond when treated with antibiotics |

| – animal has convulsions, muscle spasms, temporary paralysis |

| – gangrene or lameness is present, especially in the animal’s ears, tail and feet, which is a sign of ergot toxicity |

| – animal shows signs of heat stress, elevated breathing rate, panting or drooling |

| – animal has a fever, or has intermittent bloody diarrhea |

| – there are blisters, reddening, or ulcers in the mouth |

| – abortion and premature births occur, or reduced lactation |

| How to protect your cattle: |

| – Awareness – Monitor and address risk conditions. Reconsider feeding mouldy feeds to cattle. |

| – Feed testing – Conduct feed tests on a regular basis, particularly when feeding high risk feeds or when growing and storage conditions favour mould growth. |

| – Feed quality – Follow best practices. |

| – Keep animals healthy – Doing all you can to support healthy animals also helps make them less vulnerable to mycotoxins. If you suspect mycotoxin poisoning in your cattle, consult your veterinarian immediately. |

| Contaminated feed guidelines: |

| – The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) publishes acceptable ‘action levels’ (allowed amounts) in feed by type of mycotoxin and commodity and can be found on the CFIA website. |

| – Be aware that there is much debate in the industry about guidelines, and the bottom line is that it is not clearly known what levels of mycotoxin are acceptable for feed. There is considerable variation among species and the age of the animal are feeding can vary the results. More research needs to be done to further answer this question. |

| – When more than one mycotoxin is present in the feed, the limits of each may need to be reduced for safety, as they may have synergistic effects. |

| – Caution should be taken when following any feeding guidelines that outline acceptable levels of mycotoxin contamination, as even low levels of contamination can be harmful. |

Mycotoxins 101

For beef producers, mycotoxins are often a hidden problem. They can be invisible, colourless and odourless. They are often difficult to detect and can cause significant damage before they are identified and managed.

Mycotoxins are fungi, including mould, and can be present in the forages and other feedstuffs that cattle consume as feed. When these fungi are stressed, they have the capability to produce mycotoxins as a defense mechanism meant to protect the fungi from external threats.

Virtually all feeds that comprise beef cattle rations are potential sources of mycotoxins. This includes green pastures, cereal swaths, standing corn for winter grazing, cured and ensiled grass, cereal forages, crop co-products (straw, distillers’ grains, grain screenings, oilseed meals) and commercial feeds.

It is important to note that the fungi or mould itself is not toxic to animals. The damage is done by the defensive mycotoxins, which are secondary metabolites that the fungi produce.

More than 400 mycotoxins have been identified, but only a few are regularly found in grains and seeds used for animal feed.

A few of the most common examples of the types of mycotoxins that can be produced are:

Vomitoxin– also known as deoxynivalenol (DON), which occurs predominantly in cereal grains such as wheat, barley, corn, oats, and rye, and less often in canary seed and forage grasses. The occurrence of DON in Canada is associated primarily with Fusarium Head Blight caused by the pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Other mycotoxins which may be associated with DON are T2 and HT2, which are even more toxic than DON.

Zearalenone– Also produced by Fusarium, this less common mycotoxin is an estrogen-like compound that generally doesn’t have an effect on feeder cattle but can cause reproductive issues in cows.

Ergot is a top issue among several threats that beef producers need to manage.

Ergot alkaloids – various types can be present in the ergot body, including ergovaline, ergocornine, ergocristine, ergometrine, ergosine and ergotamine, contaminating cereal grains and cereal forages as well as cool season grasses. Claviceps purpurea is the fungus that causes ergot and produces these mycotoxins in purplish-black ergot bodies in the heads of the grasses or cereal grains. The two main alkaloids present in cereal ergot in Canada are ergocristine and ergotamine.

Threat to Beef Cattle

High temps and moisture during flowering increase the risk of Fusarium in feed.

The risk of mycotoxins being present at high concentrations in cattle feed can fluctuate substantially in any given year, based on the environmental conditions present during growth, harvest and storage. The conditions present will also dictate the potential type of mycotoxin contamination. For example, Fusarium production favours warm, moist conditions during the flowering stage. In contrast, ergot prefers cool, moist conditions during this growth stage.

The most common causes of mycotoxin issues that Canadian producers encounter are fungal diseases such as fusarium and ergot, as well as environmental, handling and storage issues that contribute to mouldy feed.

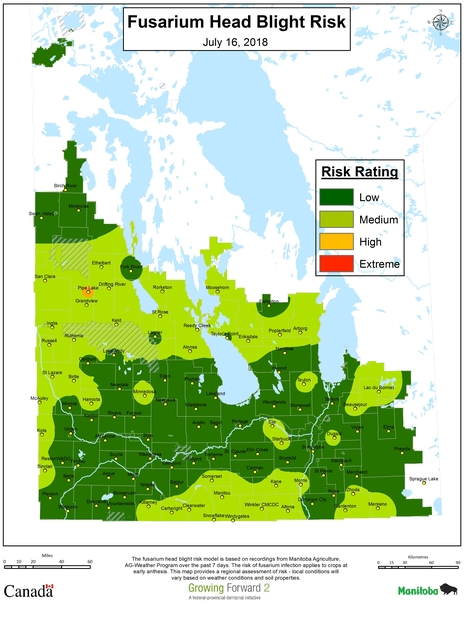

Fusarium

Fusarium has been a rising threat to feed crops in Canada. Warm, moist weather promotes spore germination on the infected crop residue that is spread by the wind to infect florets at the flowering stage of the cereal crop. In areas where fusarium is present, these mycotoxins typically present a threat to cereal grains and cereal forages fed to livestock. The threat of fusarium contamination tends to be seasonal. In addition to feed quality and feed intake issues, fusarium mycotoxins contribute to gastrointestinal irritation and immune suppression.

Ergot

Ergot has traditionally been more common in Eastern Canada but is now also rising in occurrence in Western Canada. Produced by Claviceps purpurea, ergot alkaloids can contaminate cereal grains and cereal forages as well as cool season grasses after they flower. In addition to feed intake issues, ergot alkaloids can lead to “classic ergotism” – vasoconstriction leading to lameness and eventually gangrene (sloughed hooves, tails, ears.) They also contribute to undesirable metabolic effects such as increased body temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate. This can reduce the ability of cattle to control their body temperature with animals showing signs of heat stress when ambient temperature is above 20ºC. Ergot can also lead to abortion, weak calves, and a complete lack of milk production.

Ergot in Feed: Is There a Safe Concentration for Beef Cattle?

Recent studies suggest current recommendations for ergot and deoxynivalenol limits in cattle feed may need to be re-evaluated due to toxicity risks.

Other sources

In addition, there are multiple fungal classes present in crop production and beef production areas across Canada which can impact crops, feed grains and forages and lead to mycotoxins.

Conditions leading to mouldy feed

Problems related to handling and storage of feedstuffs that can lead to mould development are another major threat. An open flap on silage can allow infiltration and feed spoilage. There’s also a risk of spread due to air contamination when spores and fungus growing on mould are released into the air. Another common issue is wet grain in storage bins that are not properly monitored and managed.

Summary – the big threats

Typically, the main mycotoxins of concern are tricothecenes (T2 and HT2, which are commonly found with DON), and ergot alkaloids. Mouldy feed is also a major feed quality issue undermining health and performance, independent of whether mycotoxins are produced by the mould.

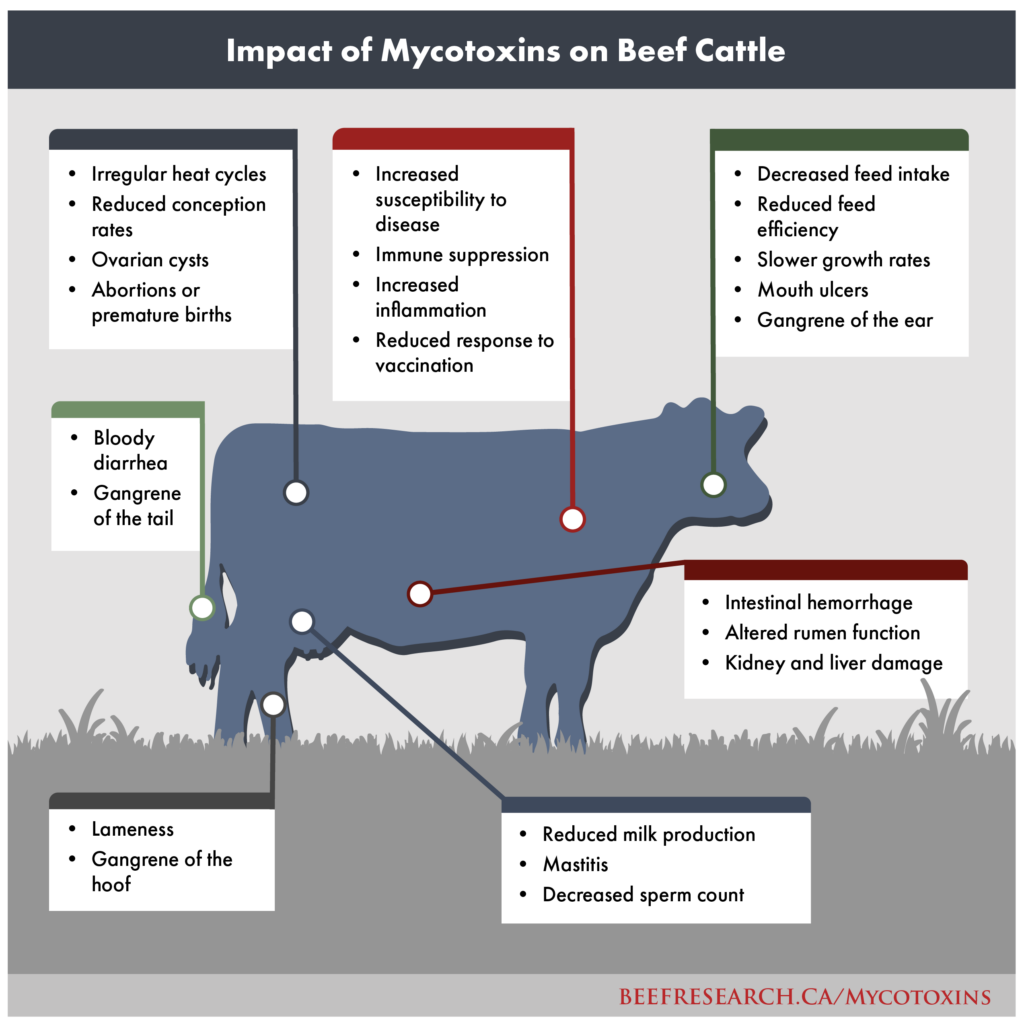

Damage to Health and Performance

Ears and tails falling off is one extreme, but many impacts are more subtle – all are costly.

Exposure to mycotoxins can have a wide variety of effects on cattle health and performance, ranging from mild to moderate to severe.

Mycotoxins can result in lower feed intake, gastrointestinal irritation, compromised nutrition, lower weight gains and even weight loss. They can lead to gut health and respiratory problems, including secondary infections, as well as reproductive issues. They can also cause immune suppression, making animals more vulnerable to other threats and reducing the effectiveness of antibiotics. They can reduce animal fertility, lead to weak calves and at high concentrations can lead to abortion in pregnant cows and major health deterioration of animals including death.

Ergot in particular can cause vasoconstriction, which results in less blood to the extremities and can cause ears, tails and feet to fall off. Ergot is particularly damaging to reproductive function as it blocks release of the hormone prolactin which is needed to maintain pregnancy as well as for milk production. For bulls, ergot-contaminated feed can reduce sperm production although overall reproductive effects are not as severe as for cows. Cattle fed ergot-contaminated diets during the winter through to spring may not shed their winter coat and can show signs of heat stress in spring/summer under environmental conditions considered adequate for cattle (20 to 28ºC).

While typically the effects are mild to moderate and often hidden, many producers may not realize the degree to which mycotoxins are reducing the productivity of their herds and leaving the animals more vulnerable to sickness and stress.

Producers may notice times when cattle back off feed consumption or when weight gains drop, for no apparent reason, without realizing the issue is mycotoxins. Similarly, producers may notice times when cattle get mild symptoms such as runny noses or show an energy drop off, again often not realizing the underlying issue is mycotoxins.

Even when the impacts are perceived as mild the related lost productivity costs can add up quickly. Not only does the presence of moulds reduce feed digestibility, but feed intake is often significantly reduced as well, resulting in impaired growth performance. Experts say the mere presence of mould or other fungi can impair digestibility up to 15 percent, even when mycotoxins are not present.

When mycotoxins are also present, that reduction in feed digestibility can rise much higher.

The Challenge of Detection

The eyeball test is not effective.

A big challenge for producers in dealing with the threat of mycotoxins is that they are often an unseen problem. The presence of fungi or mould is a noticeable indicator of a possible threat, but the mycotoxins themselves are invisible, colourless and odourless, and may be present regardless of whether or not fungi or mould are visible.

Eyeballs and experience don’t cut it when it comes down to knowing the quality of your feed. Testing for mycotoxins is the only way to know for sure.

The best options for producers are to simply not give mouldy feed to animals, to follow all best practices and precautions (see next section below) and to consider testing feed samples on a regular basis particularly when risk conditions are high (i.e. when moisture levels and temperatures are higher during flowering and when storage conditions allow moisture levels beyond recommended ranges.) If the purplish black ergot bodies are noticed in cereal grain, testing the feed is highly recommended.

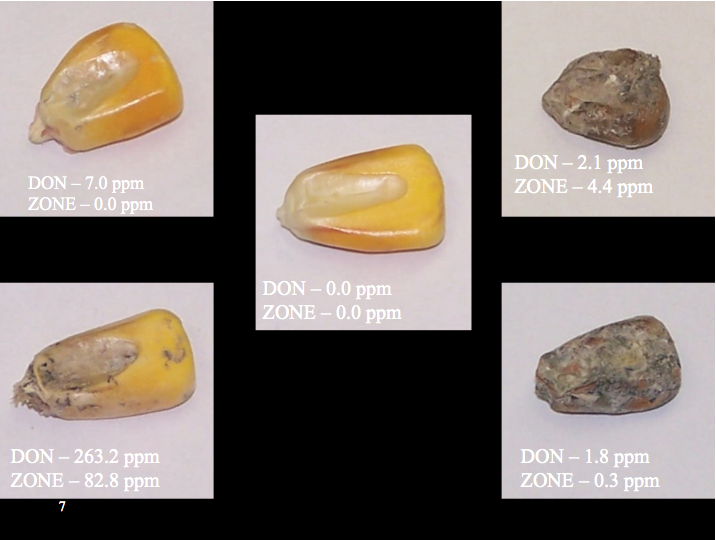

When getting testing done, it’s important to recognize that mycotoxins can be present in various degrees. Some kernels will have very high levels of toxicity while others will be lower. Therefore, getting a representative sample of feeds is VERY important. When gathering samples from feed grown on farm, it is necessary to take samples from different areas and mix them. Check with advisors and / or the test company you are dealing with for information on best sampling protocols. For example, a protocol may call for: taking five sub-samples of 250 grams each from different areas, then mixing them together in a pail, then taking 250 grams from the pail as the sample used for mycotoxin analysis.

For those purchasing feed, make sure to ask about mycotoxins with your supplier. Commercial feed mills in Canada are required to have procedures in place to identify and control potential feed contaminants, such as mycotoxins. It’s good to ask about the feed mills mycotoxin testing procedures if feeding screenings, pellets or millrun as these feeds have a higher risk of contamination.

Also check with advisors and /or the test company you are dealing with for information on frequency of testing recommendations. This can vary depending on the crop. For example, with corn in particular, you might test standing corn for mycotoxins, get low or safe results, and turn your cows out into it. In the meantime, the mycotoxins have increased greatly, and the crop is no longer safe cattle feed, despite your test results saying otherwise.

Detecting mycotoxins is a challenging endeavor and the reality is that testing options and approaches are not perfect – but the good news is they are improving all the time. The bottom line is that producers need to be careful and cautious. Test regularly. Monitor risk. Keep aware of any mycotoxin reports in your region.

| Questions to ask a feed mill nutritionist |

|---|

| Do you test finished product(s) for mycotoxins? |

| Which ingredients do you test? |

| How frequent is the testing? |

| Are all staff trained to oversee incoming ingredients? |

Closely monitoring animals and performance metrics is another important part of risk management. If you notice a change in the animals or a drop-off in intake and body condition that seems unexplained, this may be an indicator of a feed contamination problem.

How to Protect your Cattle

Reducing the risk boils down to four factors – awareness, feed testing, additional best practices to ensure feed quality and best practices to keep animals healthy.

Awareness – Monitor and address risk conditions. Awareness is about understanding and monitoring for risk factors, which can fluctuate season to season and year to year. When conditions are conducive to Fusarium, ergot and other sources of fungi and mould development greater precautions are required.

For producers growing their own feed, also consider disease monitoring from the year before as risk conditions and pathogen presence can carry over from one year to the next. For grasses used for feed, which may be infected, it’s best to mow them sooner rather than later to avoid conditions that would allow mould to develop and grow. When storing all feedstuffs, the key is to cover and store appropriately to keep moisture and oxygen levels in check. To reduce or prevent production of mycotoxins in corn, drying should take place as soon as possible after harvest. It is important to avoid damage to the kernels before and during drying, and throughout the storage period.

It’s also important to monitor livestock for early symptoms of mycotoxin related issues. If symptoms such as an unexplained drop-off in feed intake or weight gain, or a rise in gastrointestinal issues, appear to happen for no reason the cause could be mycotoxins and you should test your feed to see if contamination may be the problem.

Feed testing – Do it regularly. It’s important to remember that mould and mycotoxins are not the same thing. Mycotoxins may still be present even if no mould is visible. It is difficult to correlate mould or grain damage with the presence of mycotoxins. The only way to know for sure is feed testing for mycotoxin identification.

Regular feed testing is now advised as a standard part of good management that provides a valuable insurance policy and peace of mind.

While accurate rapid tests exist for the presence and levels of mycotoxins and others, one current challenge is the lack of a rapid test to quantify the level of specific ergot alkaloids. The Canadian feed industry has implemented approaches to help address the ergot issue by pre-screening incoming ingredients and limiting the use of certain risk ingredients in years where higher levels of ergot are suspected or known.

Feed quality – Follow best practices. Ensuring feed quality also means following best practices:

- Practice regular feed testing – remember visual appraisal is unreliable

- Never feed mouldy feed to pregnant animals

- Purchase cereal by-products (cereal screenings and distillers’ grains are higher risk) from reputable feed sources and test for mycotoxins prior to feeding if you are unsure

- Remember forages can be contaminated too

- Source quality “clean feed” from trusted sources (feed mills, feed suppliers, etc., who have strong quality control measures in place)

Keep animals healthy – Multifactorial approach. Doing all you can to support healthy animals also helps make them less vulnerable to mycotoxins. Make sure to follow best practices for:

- Herd health (vaccinations, parasite control, routine monitoring)

- Biosecurity

- Clean, safe environment

- Nutritional status & feeding management

- Reduce stress (animal care and welfare best practices)

- Gut health

Use industry resources and trusted advisors to support your approaches in all of these areas.

Summary note – Do your homework. With all feed technology options there are a range of preventative sources with varying quality and efficacy. Do your homework and rely on trusted advisors to ensure you are using options based on sound science and proven results.

Digging Deeper on the Big Questions

What are the top challenges mycotoxins present?

- Animals given mycotoxin-infected feed can experience many health problems, some of which are severe

- Feed management strategies (such as testing, cleaning or diluting feed) can cost the producer time and money

- Although more than 400 mycotoxins are known, commercial testing is only available for a few of the most common

- Infection can degrade market quality of grain, causing significant financial loss for a producer growing crops for feed

- In extreme cases, infected feed may need to be thrown out and replaced.

In 2015, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) prepared an assessment of mycotoxin contamination in feed and estimated its cost to the industry in North America.

“It has been estimated (Miller, Personal communication), for example, that annual losses in the USA and Canada, arising from the impact of mycotoxins on the feed and livestock industries, are of the order of $5 billion.” – FAO, 2015

Mycotoxin contamination is difficult to trace and measure. Likewise, field data and research into the effects of mycotoxins in cattle can be variable and contradictory. Mycotoxins rarely occur in isolation, yet the combined effects of different types of mycotoxins are not well-known.

If feed ingredients are contaminated with mycotoxins, degree of toxicity can be difficult to determine. Total mixed rations (TMR) using multiple ingredients can make it even more difficult to determine the extent of toxicity and pinpoint the cause. With other manufacturing processes, such as distillers’ grains, toxins can quickly add up to unsafe concentrations.

Further research is needed to fully understand how to control mycotoxins, and to determine what concentrations are ‘safe’ in feed for cattle.

Mycotoxins affect animals in a variety of ways, depending on their age and stage of life, the extent of mycotoxin exposure and the length of time the animal has ingested a certain mycotoxin, and the type of diet (high forage or high concentrate) cattle are fed.

Eliminating the threat of mycotoxins is nearly impossible. However, producers can take preventative steps to reduce the possibility of mycotoxin contamination of their feed sources. If mycotoxins are detected in feed grains, certain strategies can be followed to make the feed source safer for cattle.

Cattle, being ruminants, are considered somewhat resistant to mycotoxin. This is due to the microbes in the rumen naturally being able to detoxify a consistently low concentration of some mycotoxins over time. However, this is not true for ergot alkaloids as cattle are much more sensitive than swine and poultry. Additionally, if sudden high concentrations of mycotoxins are present in the feed, the negative impact on animal health can be severe.

Where are mycotoxins found in Canada?

In recent years, Canadian producers have seen increased occurrence of mycotoxin contamination from fungi such as Claviceps purpurea and Fusarium graminearum.

In 2005, widespread ergot mycotoxin contamination was noted in Manitoba, followed by similar outbreaks in 2008 and 2011 across Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta. Claviceps purpurea is more often found in the western Prairies. Cattle have a lower tolerance for ergot alkaloids than they do for the mycotoxins that result from Fusarium.

Fusarium has traditionally been found in Eastern Canada and the Midwest United States, but a severe outbreak in 1993 made the disease more prevalent in Manitoba and Eastern Saskatchewan. Since 1999, Fusarium has continued to spread into Western Saskatchewan, Alberta and Northern British Columbia.

What causes mycotoxins?

Mould growth, and the subsequent potential production of mycotoxins, is typically the result of plant exposure during flowering and tends to be worse when conditions produce a wet, cool spring. Drought can also stress plants and make them more susceptible to fungi such as Claviceps purpurea and Fusarium graminearum.

Ergot bodies produced by Claviceps purpurea can also drop from infected plants onto the soil. These ergot bodies then germinate in the spring and release spores which enter the plants at the flowering stage.

The complex ecology of mould growth, and subsequent mycotoxin production, can produce a staggering variety of toxins. These moulds multiply in the field, and mycotoxins can also be ‘imported’ within the feed itself. Left undetected, many of these mycotoxins can make their way into feed sources for cattle at dangerous concentrations.

While the mycotoxins resulting from Claviceps purpurea and Fusarium contamination pose significant challenges for producers, the diseases caused by these mycotoxins have different characteristics.

What are the mycotoxin-specific best practices?

The effect that mycotoxin-contaminated feed can have on cattle depends on what type of mycotoxin is present, the age and production stage of the animal, the amount that the animal has ingested and how long the animal has been consuming contaminated feed. Calves born after exposure to mycotoxins may be permanently set back, although generally cattle should rapidly recover once the mycotoxins are removed from the diet. Reproductive functions such as milk production might not recover until the next pregnancy.

Here are some best practices to employ when you suspect mycotoxins in your field or feed.

Identify Crop Disease

Identify crop diseases early, especially those from Claviceps and Fusarium that produce mycotoxins. Each crop disease will express differently, so get to know what to look for in your field. Catching the disease early can help to reduce the chance of mycotoxins entering the feed. More complete information can be found in the sections on ergot and Fusarium mycotoxins below.

Symptoms of Mycotoxin poisoning

Watch for symptoms of mycotoxin poisoning in cattle. Paying close attention to your livestock is key. One of the difficulties is that cattle with mycotoxin exposure express symptoms that are wide and variable, and those same symptoms can also relate to other problems. Younger animals, such as calves just weaned and starting on feed, or heifers at breeding, are more susceptible to poisoning because of their immature immune systems and lower ability to metabolize toxins. These groups of cattle must be watched carefully for signs of distress.

Some problems from ingesting mycotoxins are reversible, while others can be very serious, even leading to death.

Here are some general signs that your cattle could have mycotoxin poisoning. Trust your experience – if you feel ‘something is not right’, it probably isn’t. Take immediate action if an animal exhibits any of these symptoms (symptoms are most often seen in the winter months):

- animals consume less feed; a feed reduction greater than 30% should be investigated

- a decrease in growth or performance, or a failure to thrive

- animal seems to be frequently sick, which may indicate immune suppression

- animal does not respond to antibiotics

- animal has convulsions, muscle spasms, temporary paralysis (not typically seen in Western Canada)

- gangrene or lameness is present, especially in the animal’s ears, tail and feet

- animal has a fever, or has intermittent bloody diarrhea

- heat stress, elevated breathing rate, panting and drooling

- there are blisters, reddening, or ulcers in the mouth

- abortion and premature births occur, or reduced lactation

- fertility issues such as weak testicular development and low sperm count in bulls.

Actions to Take if You Suspect a Mycotoxin Infection

>> If you suspect mycotoxins in the feed, remove the feed immediately, and do not feed it until it’s been properly tested in a lab or diluted or cleaned to acceptable levels.

>> If you suspect mycotoxin poisoning in your herd, consult your veterinarian immediately.

Feed Sources

Know the source of your feed ingredients. Some feed processing procedures can concentrate or increase mycotoxins in the feed (e.g. grain screenings and distillers’ grains). This can take a contaminated feed source from ‘safe’ levels to ‘high risk’ levels quickly. While most livestock feed manufacturers will screen for mycotoxins, it’s important to ask where the crop ingredients originated from, and whether it is from an area known to have high levels of mould growth, plant stress or mycotoxin contamination. Make sure you alert your whole team to be on the lookout for this problem. Keep your veterinarian, nutritionist and feed company reps in the loop.

Testing

If you suspect an infected crop or contaminated feed, get a lab test to confirm the extent of the problem. Allow several days for the lab to complete the test. If you operate in a high-risk area or have had issues in the past frequent testing may be a good prevention strategy even if contamination is not suspected this year.

For a list of labs in your province, consult the Canadian Grain Commission, your local agriculture specialist or search online. Costs will vary depending on the test required, so check with the lab.

| Getting a Good Sample to Send to the Lab |

| Mycotoxins are rarely evenly distributed, so getting a representative sample can be challenging. The accuracy of your lab results will depend on the quality of the sample you submit. Here are suggested steps for getting a good sample. More than 90% of the variability that is seen in the lab is due to sample collection. |

| HARVESTED GRAIN |

| – take 15 to 20 samples during loading and unloading, or 1 to 4 spots in the grain bin |

| – aim for a sample of 1,000 to 2,500 grams |

| – clean the sample to remove weed seeds, rocks and other material – mix these samples in a container and collect a final sample of about 500 grams from the mixture (or the required amount for the lab you are using) |

| – send to the lab in a Ziploc bag with your name and paperwork attached |

| FIELD SAMPLES |

| – close to harvest time, combine a swath from a typical section of the field, or collect an average of 5 to 10 plants from various locations throughout your field by cutting off the plant about 4 to 5 inches above the ground |

| – chop the samples into smaller pieces, and mix all the samples from the 5 to 10 plants together |

| – fill one-half to two-thirds of a bread bag (or a large Ziploc bag) and squeeze all the air out of it |

| – freeze the sample, label the sample and attach the required paperwork |

| – Mycotoxins are stable, so it is not imperative to ship the sample to the lab immediately |

Handling

Take precautions when handling infected crops or feed. Mycotoxins present in crops or feed can not only be dangerous for animals to consume but can also be hazardous for producers to handle and/or inhale.

Use these precautions when handling infected seed or feed:

- stay away from dust clouds when processing feeds

- wear a new, well-fitting N-95-rated breathing mask

- wash your hands thoroughly after handling infected kernels

- if you’ve been handling infected grain and feel unwell, watch for signs of fever, skin irritation, asthma-like, or flu-like symptoms, and advise your doctor if symptoms persist.

Prevention

Preventative measures reduce the risk that cereal grains will be infected with mycotoxins. Crop rotation, summer fallow and fungicides may be suitable treatments for infected areas. However, it is strongly encouraged to seek professional advice prior to the application of any commercial products.

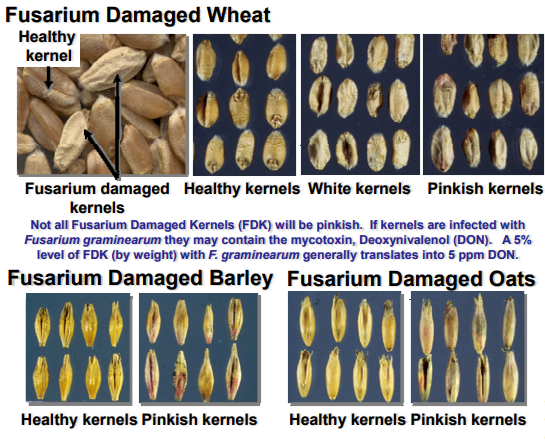

Fusarium head blight (FHB) is a fungal disease that affects kernel development. It is most common in wheat, barley and corn, but can also occur in oats, rye, canary seed and forage grasses. FHB is caused by several species of Fusarium, but the most aggressive type is the fungus Fusarium graminearum (FG).

Fusarium tends to favor more humid regions of North America, and is found most frequently in Eastern Canada, plus in the black soil zones in Western Canada where the Prairies’ highest rainfall occurs. Irrigated crops at the flowering stage are also associated with the disease.

Fusarium mycotoxins are at their highest concentrations in the early stages of kernel development (two to three weeks before seed maturity). Infection is associated with rainfall during the flowering stage. FG is spread in many ways: the spores are carried on the wind, the disease is spread through rain splash, or by infected grain, straw or seed.

Under certain conditions, different Fusarium-related mycotoxins can be produced. Deoxynivalenol (DON) is the Fusarium mycotoxin detected most often. Sometimes referred to as vomitoxin, DON is considered a mild toxin, compared to other toxins that form in grains and forages.

Typically, cattle dislike the taste of Fusarium-infected feed, so they tend to avoid it. For example, cattle feeding on standing corn tend to eat the stems and leaves of corn plants, but not the cobs when Fusarium mycotoxins are present.

If cattle ingest DON, they can metabolize low levels of DON from their system without incident, but we don’t yet know the levels of DON that overwhelm the rumen. The DON mycotoxin is poorly absorbed by ruminants and cattle are usually able to metabolize it efficiently. However, the rumen pH must be stable for this to occur, something that is not easy to maintain, especially when using extended grazing systems or when feeding high concentrate finishing diets.

Although cattle can detoxify DON, the presence of DON may indicate that other potential fungal toxins are also present. Less is known about the interactive effects of other Fusarium-related mycotoxin classes such as T-2, HT-2, DAS and fusaric acid.

What to do if you suspect fusarium poisoning in cattle?

Cattle consuming a combination of Fusarium-related mycotoxins can experience mouth blisters, hemorrhaging in the gastrointestinal tract, and depressed immune system function which leaves the animal more susceptible to other infections. Pregnant cows and young calves are more sensitive to Fusarium mycotoxins.

Although it is unlikely that an animal will die from ingesting mycotoxins caused by Fusarium, these mycotoxins can still cause problems for cattle. The good news is that many symptoms are reversible.

Symptoms – DON poisoning

If you suspect DON poisoning in your herd due to Fusarium, remove the feed immediately and call your veterinarian. Symptoms are typically intermittent, vague and observed in the winter. Here’s what to look for:

- Reduced feed intake, or eating partial feed

- Drop in growth or performance

- Lower milk production

- Blisters in the mouth

- Bloody diarrhea

- No response to antibiotics

- Suppressed immune system, poor doers

- At high concentrations, pregnant cows may have abortions.

Identifying Fusarium in a Crop or Harvested Grain

The correlation between the extent of mould present and the degree of mycotoxin contamination is poor. Therefore, it is important to have the feed tested for mycotoxin concentrations.

Fusarium shows up as an ear rot in corn and scab or head blight in cereals. Infected plant spikelets have bleached heads with shriveled chalky or pinkish kernels (in wheat) or an orange or black encrustation of the seed surface (in barley). A fluffy fungal growth may be evident on infected heads, and orange, spore-bearing structures called sporodochia can be evident at the base of the glumes. Any of those symptoms indicate that you should test for mycotoxins because the correlation between the extent of mould present and the degree of mycotoxin contamination is poor.

The seeds in blighted heads appear shriveled and bleached, and do not fill in properly. For more information on identifying Fusarium head blight in cereals, see this Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada information sheet.

Management strategies for Fusarium-infected feed

Testing

If you suspect a Fusarium infection, be safe and get a lab test done. Although the blight is readily visible, the harmful mycotoxins are impossible to spot. The only way to know for sure if mycotoxins are present in feed, and their degree of toxicity, is to have grain or feed analyzed by a lab. See the Best Practices section above for details on lab testing.

Feeding based on test results

Once you know the levels of DON (or other toxins) in the feed, follow recommended guidelines to make sure it is safe to feed.

According to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada guidelines adult beef cattle diets should have no more than 5 ppm of DON. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) also publishes acceptable ‘action levels’ (allowed amounts) in feed by type of mycotoxin and commodity. These mycotoxin regulations for Canada can be found on the CFIA website.

However, be aware that there is much debate in the industry about the guidelines, and the bottom line is that it is not clearly known what levels of mycotoxin are acceptable for feed. Additionally, maximum levels should be reduced when more than one mycotoxin is present in the diet.

There is considerable variation among species. Dairy cattle, in particular, are often more susceptible than beef cattle. The age of animal you are feeding can vary the results, and differences have been observed between the breeds of beef cattle. More research needs to be done to further answer this question.

Caution should be taken when following any feeding guidelines that outline acceptable levels of mycotoxin contamination, as even low levels of contamination can be harmful.

Dilution

Another option is to dilute infected feed with clean feed to make it more palatable. If you are using a dilution strategy, be sure of the level of infection you are dealing with by having the feed lab-tested. If you plan on ensiling the crop, note that this does not decrease the concentration of Fusarium mycotoxins.

Composting residues

If you use grass hay or straw residues in your field for bedding livestock, be aware that if the straw is infected with Fusarium, you run a high risk of spreading the disease. To kill Fusarium in the residue, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry’s Alberta Fusarium graminearum Management Plan recommends composting infected residues to a temperature of 60°C to 70°C for two weeks. For more information on farm composting, visit the FAO website.

Prevention strategies for Fusarium in the field

As with ergot, it’s best to take preventative measures. These strategies will help minimize Fusarium-related mycotoxin concentrations:

- use healthy seed proven to be free of Fusarium

- it is highly recommended, but not required, that all seed produced in Alberta be treated with a fungicide

- all imported cereal seed must be treated with a fungicide seed treatment registered for control of seed-borne Fusarium

- varieties with improved levels of resistance are available, but will not eliminate the risk completely

- stagger planting dates for cereals so not all plants are flowering at the same time

- during the growing season, check fields for the presence of this disease

- irrigate crops before they flower as watering during flowering can make crops more susceptible to Fusarium

- apply a fungicide at an early flowering stage if the risk of Fusarium is moderate to high; this will not eliminate the disease, but may provide suppression

- watch for premature bleaching of grain heads, which could indicate a Fusarium problem

- rotate crops to keep host plants out of the rotation for at least three years

- using corn in rotation with small cereal grains has been shown to increase Fusarium, as corn stubble can harbor Fusarium fungi that may result in Fusarium head blight in barley and wheat.

- properly dry and store grain, as high moisture content increases the likelihood of Fusarium, and therefore mycotoxin contamination. (This doesn’t work for ergot as it is fully developed before storage.)

The major ergot fungus is Claviceps purpurea which produces sclerotia (commonly called ‘ergot bodies) in several grass species. Ergot is present in cereals and grains throughout the world, but is most typically found in rye, triticale, wheat, barley, oats and some perennial or wild grasses. Although Claviceps purpurea is not found in corn, other mycotoxin-producing fungi can contaminate corn and can cause problems when fed to livestock.

Once mature, the ergot sclerotia (the hard, purplish black body of the fungus) becomes detached from the host plant, drops to the ground and can remain dormant in the soil until favorable growth conditions occur.

Ergot contamination of cereals can occur in two stages. During the first stage, the sclerotia germinates and produces fruiting bodies resembling a tiny mushroom. These bodies produce thread-like spores that are wind-blown to the host plant. The plant’s florets must be open to be infected. Cool, damp weather during the flowering period can prolong the flowering stage, and make a plant more susceptible to infection, and thus the spread of disease.

Once a plant’s florets are infected, within about 5 days, a secondary spore growth occurs in the plant head along with a second chance at spreading the disease. These spores are encased in a sticky liquid referred to as ‘honey-dew’. This liquid can be spread by rain splash or insects that spread the spores further throughout the crop.

As the infected plant grows, the sclerotia matures and hardens into elongated, dark or black kernels (ergot bodies) that resemble mouse droppings. Left to mature, these ergot bodies will detach from the plant head and drop to the soil, starting the cycle over again.

If these ergot bodies are harvested along with the grain, however, the ergot bodies can enter the feed system. These dark ergot bodies contain toxins called ergot alkaloids. When consumed, these alkaloids can be harmful to cattle, causing irritability and more severe conditions such as gangrene of the ears, tail and feet. Cattle can also show signs of heat stress like elevated breathing, panting and drooling at low ambient temperatures (above 20ºC), which are not normally seen. Young or pregnant animals are more susceptible to ergot poisoning.

What to do if you suspect ergot poisoning in cattle?

Ergot poisoning can be very serious. The symptoms of ergot toxicity can be acute (24 hours after ingestion) or take between two and six weeks after an animal ingests ergot-infected feed. Some symptoms such as gangrene, once manifested in an animal, are irreversible. Therefore, preventative measures are essential.

Symptoms of ergot poisoning

If you suspect ergot poisoning in your herd, remove the feed immediately and call your veterinarian. Here’s what to look for:

- Convulsions, muscle spasms, temporary paralysis

- Lameness, usually observed in the hind legs first

- Gangrene especially in an animal’s ears, tail and feetFeverThe time for gangrene to appear will be influenced by the concentration of ergot in the feed and the ambient air temperature. Under extreme cold or heat, increased feed consumption and the combined vasoactive effects of cold, heat and ergot result in clinical manifestation at lower concentrations.

- Heat stress symptoms such as elevated breathing rate, panting and drooling

- Elevated body temperature (more so during the summer or the hottest hours of the day)

- Abortion and premature births

- Reduced milk production (usually persists for the entire lactation period)

- Animals consuming less feed, and generally failing to thrive.

Identifying ergot in a crop or harvested grains

Ergot can appear in seed heads of annual crops used for green feed, swath grazing or bale grazing, and can persist for up to a year (or longer) in stored grain or in the field. Ergot toxins can also be more highly concentrated in distillers’ grains, screenings and screening pellets.

Dark or black elongated ergot bodies grow in place of the kernel. Ergot kernels can vary greatly in size, and can be much larger, the same size, or smaller than healthy kernels. A visual test will show the presence of the sclerotia, but a lab test is needed to determine the concentration of the alkaloid toxins. Ergot bodies may have different concentrations of alkaloids, and these concentrations can vary from crop to crop. For a visual reference of ergot, read our blog.

Management strategies for ergot-infected feed

The only way to know for sure if mycotoxins are present in feed, and to evaluate the risk of toxicity, is to have feed analyzed in a lab. An individual ergot body can have high or low levels of toxins, so testing is the only sure way to determine the concentration of the mycotoxins. See the Best Practices section above for details on lab testing.

It may be possible to clean infected feed by separating it from healthy grain by size, colour or by gravity cleaners. However, this process can be slow and/or expensive. For more on this, read our ergot blog.

If you are attempting to improve contaminated feed by diluting it with clean feed, or you are wondering what is ‘safe’ to feed your animal, be aware that ergot poisoning may occur at concentrations lower than those stated in previous guidelines.

There is much debate in the industry about the guidelines, and the bottom line is that it is not clearly known what concentrations of ergot alkaloids are acceptable for feed. It can vary depending on the type of ergot alkaloid present, season of the year, diet being fed, or the age and breed of cattle. More research needs to be done to further answer this question.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) publishes acceptable ‘action levels’ (allowed amounts) in feed by type of mycotoxin and commodity. These mycotoxin regulations for Canada can be found on the CFIA website. Again, these guidelines are to be used with caution because many in the industry believe that these recommendations are outdated and they are currently under revision. According to CFIA guidelines beef cattle should not be fed more than 2 to 3 ppm of total ergot alkaloids in the diet. However, recent work funded by the BCRC has shown reduced intake and weight gains when cattle were fed 1.5ppm total ergot alkaloids in the diet (DM basis). It is recommended to keep total ergot alkaloid levels in the diet below 1 ppm to prevent growth performance losses and toxicity signs.

Check with your lab, your vet or other feed experts on what is the most current research on offering contaminated feed to your animals. However, with this kind of uncertainty, you may not want to take the chance. In the end, it may be more economical to buy new feed if you discover heavy contamination in your feed and dispose of any infected feed.

Prevention strategies for ergot in the field

Ergot can be difficult to spot until the disease is well underway. By the time the ergot bodies are visible, it is too late to stop the impact on the crop. Therefore, if you are growing crops for feed, it’s best to take preventative measures to try to minimize fungal disease before it takes hold on the farm. Once ergot infects a field, it is difficult to eradicate.

The following management practices can help reduce the chance of the disease gaining hold in a crop:

- grazing animals on pasture is safer, as it is difficult for ergot to take hold when the plant is eaten before it heads out

- if you graze animals on pasture with grass that has already headed out, check for ergot infection before allowing your animals to graze

- mow grasses in neighbouring fields, roadways or ditches

- plant seed that is free of disease, or choose a seed variety with a higher resistance to disease

- use practices that keep soil and crops healthy, such as tillage practices that may reduce infestations

- rotate crops away from infected crops to avoid carry-over of mould and sclerotia

Canadian Research on Ergot and Fusarium Mycotoxins: What Does the Science Say?

Due to the ability of cattle to detoxify DON, most Fusarium-related mycotoxins have traditionally been regarded as a less severe problem as compared to ergot-related mycotoxins. Canadian standards are available for feeding cattle a ‘safe’ concentration of ergot alkaloids and Fusarium-related mycotoxins, but many livestock specialists feel they are outdated and lack Canadian relevance associated with temperature, moisture conditions and crop types.

The complexity of this issue means more research is needed for clear guidelines moving forward.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at [email protected]

Acknowledgements

Thanks to

- Dr. John McKinnon, Beef Industry Research Chair, University of Saskatchewan,

- Dr. Barry Blakley, University of Saskatchewan

- Dr. Kim Stanford, researcher with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development,

- Amanda Van De Kerckhove, Ruminant Nutritionist, Federated Co-operatives Limited,

- Sean Thompson, Feed Industry Liaison, Canadian Feed Research Centre,

- Cedric MacLeod, Executive Director, Canadian Forage and Grasslands Association, and

- Dr. Gabriel Ribeiro, Saskatchewan Beef Industry Chair, University of Saskatchewan,

for contributing their time and expertise during the development of this page.

Ce contenu a été révisé pour la dernière fois en Décembre 2023.