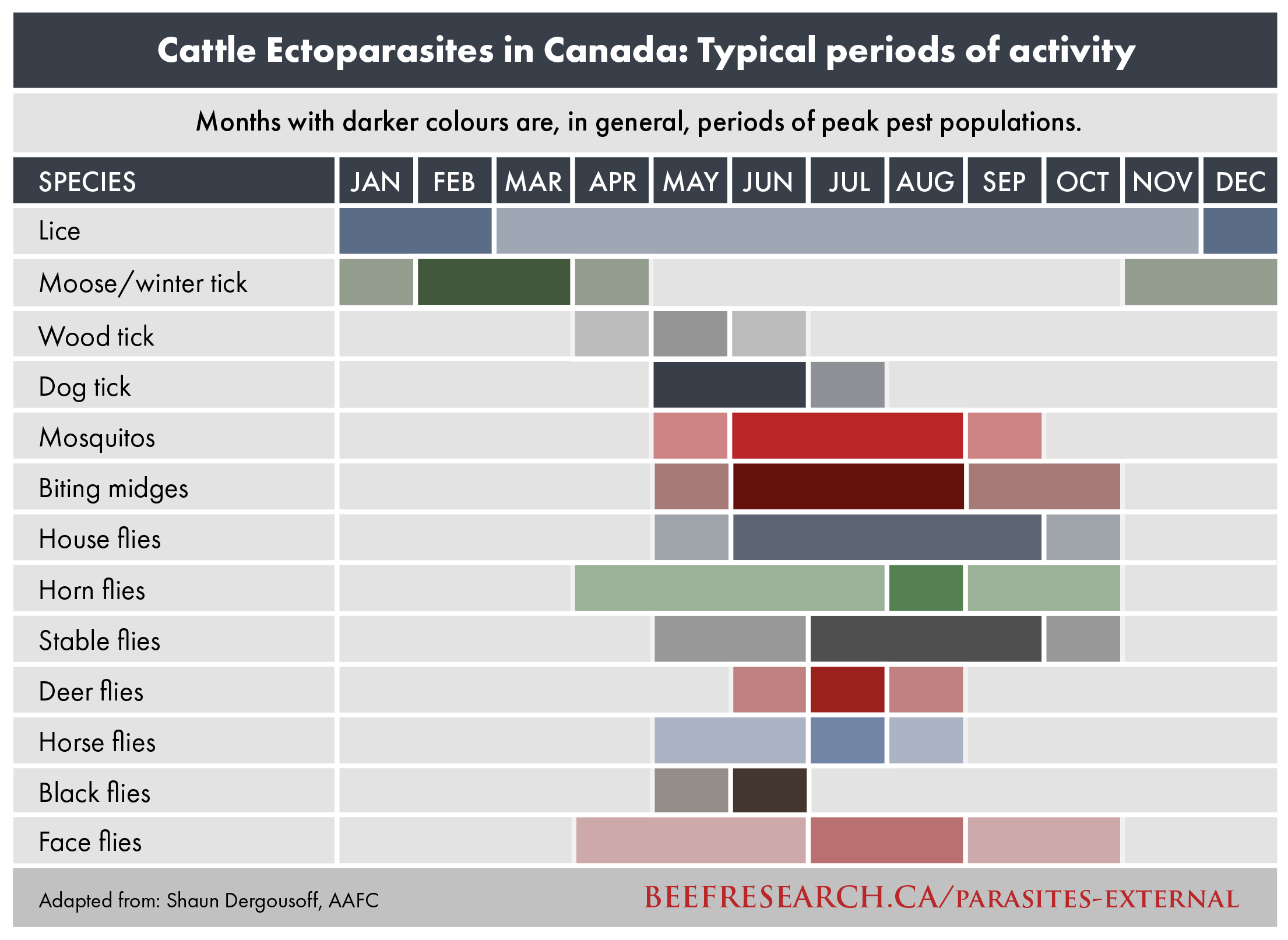

External parasites, also known as ectoparasites, live on and feed off their host animal and can cause an animal stress, production losses, irritation and injury. Common external parasites that affect beef cattle in Canada include lice, ticks, and flies. Different species of parasites can cause livestock problems during different seasons.

Understanding external parasites and monitoring their activity will help producers implement effective management and control strategies that mitigate the impact of external parasites on animal health, welfare, productivity and profitability.

Click to visit BCRC’s internal parasite page.

| Key Points |

|---|

| External parasites can cause irritation, stress, production losses, and affect grazing behaviour in the host animal when pest populations are high. |

| External parasites can carry and transmit livestock diseases such as pinkeye or anaplasmosis from one animal to another. Parasites can also be vectors for human diseases like West Nile disease or Lyme disease. |

| To effectively manage external parasites, producers must identify the problematic pest. There are at least thirteen different species of flies, lice, and ticks that can affect beef cattle production in Canada. |

| When bringing new cattle into a herd, producers should isolate, inspect and treat incoming cattle for external parasites prior to combining groups. |

| Some types of parasites, such as horn flies and ticks, generally affect grazing cattle. Other parasites, such as lice and stable flies, primarily affect confined livestock. |

| When evaluating control measures, a combination of physical, cultural, mechanical, and/or chemical methods should be used to effectively manage pests. This is referred to as integrated pest management (IPM). |

| To maximize control and prevent the development of pesticide resistance, producers should: |

| First, check the cattle to make sure that external parasites are the cause of the problem; |

| Always follow label instructions; |

| Apply the correct product for the target species at the appropriate time of year and the proper dosage; |

| Alternate between parasite control product(s) with different modes of action and active ingredients to slow resistance; |

| Monitor pest populations following treatment to assess effectiveness. |

Parasites, both internal and external, can cause production losses and discomfort to livestock, and are an economic and welfare concern.

External parasites can lead to stress, reduced weight gain, decreased milk production and other production losses, irritation, and injury in their host animal. Parasites can also alter grazing and feeding behaviour in beef cattle. Some parasites transmit cattle diseases, such as bluetongue, pinkeye, and bovine anaplasmosis, from one animal to the next. Parasites can also be vectors of human diseases, and can carry problematic illnesses such as Lyme disease, West Nile disease, and equine encephalitis.

There are at least thirteen different types of external parasites that affect beef cattle in Canada. These include chewing lice, three species of sucking lice, three species of ticks, horn flies, stable flies, face flies, house flies, and multiple other species of biting midges, mosquitoes, horse flies, deer flies, black flies and mange mites.

Some pests cause problems in particular regions in Canada while not in others. Confinement situations can intensify certain pest problems. For example, species of lice may be present year-round; however, they can spread quickly through a herd kept in close proximity to one another during the winter. Stable flies are another problematic pest in confinement situations as they have preferred development habitats such as manure piles and spoiled feed. Other pests, such as horn flies, are more of a nuisance in grazing scenarios.

External Parasite Prevention and Control Measures for Beef Cattle

The goal of pest control is not necessarily to eliminate the pest entirely. Rather, management strategies for preventing and controlling external parasites should be designed to reduce pests to populations below the level at which they cause production losses and harm to livestock.

Integrated Pest Management

Integrated pest management, often referred to as IPM, combines preventative measures to keep pest populations low, and then treatment strategies when the pests become a problem. Multiple different control measures, including physical, cultural, mechanical, and/or chemical, may be used to reduce pests to a point that is below a threshold where producers would start to experience economic losses.

Effective IPM strategies require that producers assess and identify the pest they are dealing with on their farms and gain an understanding of the magnitude of the problem. Producers can monitor for pests by using traps or visual observation and assess animal behaviour for indications of irritation and problems. Pastures or confinement areas should also be examined for suitable habitat or development sites that pests may live in.

Producers should keep good production records of pest control products they use each year and season so they can quickly assess information when they need it.

The next step of IPM is to evaluate options for control. There are three main types of control options, including biological, cultural and chemical. Biological and cultural control methods are important for preventing and reducing the frequency and intensity of pest population outbreaks. Biological controls include any living organisms that kill the pests, such as other insects, animals, or fungi. Cultural controls include physical, mechanical or other preventative practices that reduce sites favourable for pest development. Practices such as sanitation, water and manure management, and eliminating spoiled feed and silage, are common cultural controls used to help reduce pest development sites. Chemical control is a common method of controlling pests, but it is critical to understand the timing, mode of action, and class of insecticide used. Determine whether the insecticide has long-term or short-term efficacy and consider withdrawal periods.

Once producers implement control strategies, it’s important to monitor pest populations to determine whether management efforts were effective. Pest populations should also be monitored to determine if retreatment is needed. This includes assessing animal behaviour to see if they are less irritated and more comfortable.

- Identify and assess the pest

- Evaluate control options

- Implement control strategies

- Monitor effectiveness following treatment

Common External Parasites Affecting Beef Cattle in Canada

External parasite problems can depend on the type of beef production system, geographic location, management practices, and the time of year. Parasites also need species-specific development habitat (i.e. brushy vegetation, standing water, or fresh manure) to complete their life cycles.

The life cycle of each pest determines when they are active throughout the year. The timing of adult activity overlaps for several types of pests, so producers should be aware of what pests are present in their region. The timing of pest activity can vary throughout the day. Some pests are active at the same time, and cattle can be irritated by several different parasites simultaneously, causing a substantial change in behaviour and production losses. Also, some types of pests are active at different times of the day (and night), and animals may have little rest from parasite pressure.

The following webinar explains external parasites, including the principles of integrated pest management (skip to 9:46), horn flies (skip ahead to 22:41), ticks (go to 30:19), house and stable flies (playing at 36:10), and lice (skip to 41.39). Near the end of the webinar there is more information about parasite resistance and management strategies to prevent resistance (go to 46.57).

Video: Prevent External Parasites from Bugging Your Cattle

Correctly identifying the pest that is causing production problems is an important first step to proper management and prevention strategies.

Lice

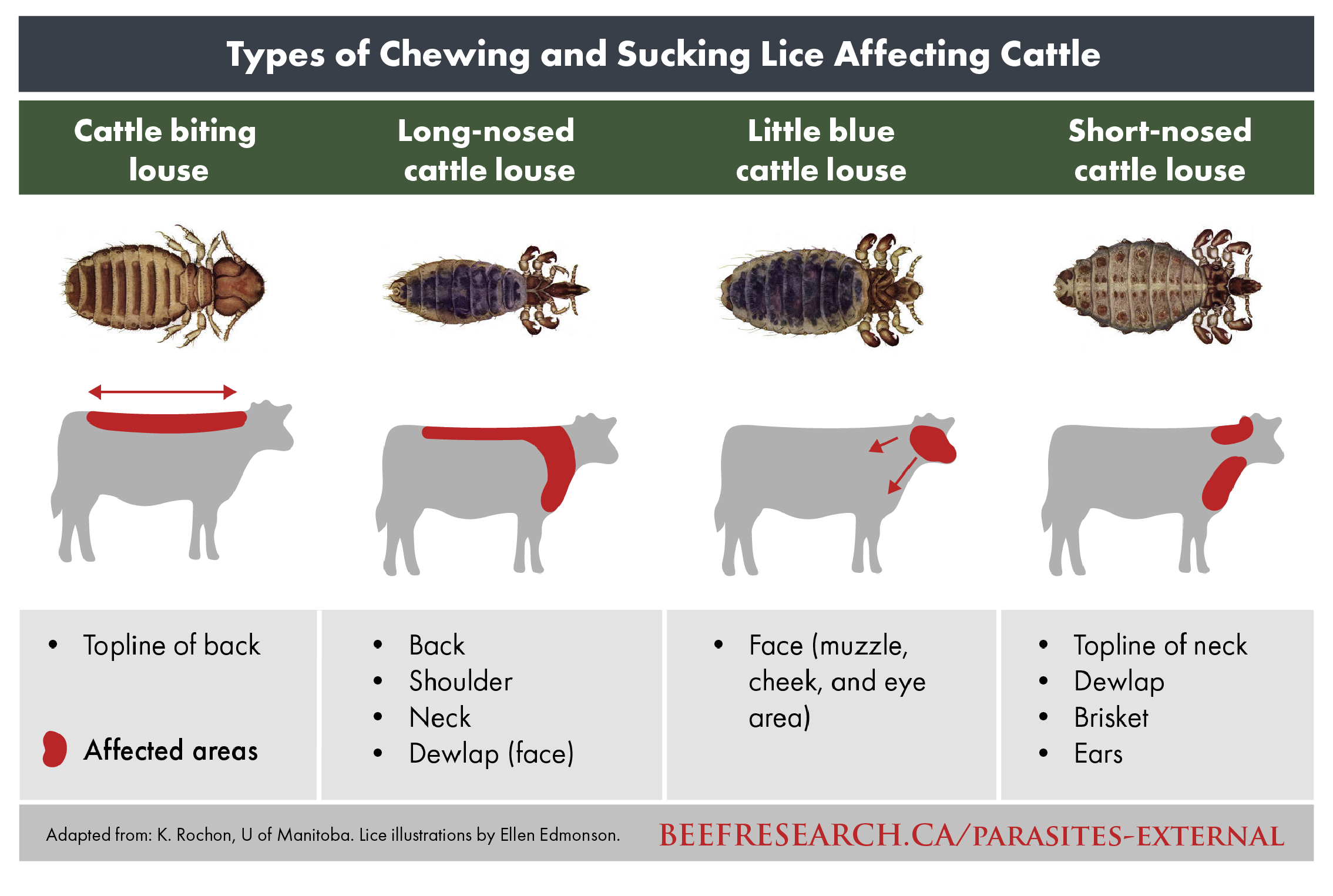

There are two types of lice that affect beef cattle, chewing lice and sucking lice. Chewing lice (also sometimes called biting lice) consume dead skin cells and oil secretions. Chewing lice can survive on the animal host longer than sucking lice can, which may cause infestations to build up in spite of treatment. They are often found on the topline and flank of affected animals. The cattle biting louse is the only species of chewing lice that affect Canadian cattle.

Sucking lice consume blood sucked from the capillaries which can cause more serious production problems including anemia. There are three species of sucking lice feeding on cattle: the long-nosed cattle louse, the little blue cattle louse, and the short-nosed cattle louse. Sucking lice can also feed anywhere on the body but are typically found along the head and shoulders of affected animals.

With lice infestations, it is important to identify the type of lice and how big of a problem the pests are causing. Hair loss and hide damage, and behaviour such as rubbing, licking, and vigorous scratching, are all signs of lice but producers can’t assume hair loss or itchiness is due to lice without proper identification.

To diagnose lice, producers should restrain an affected animal, use a bright headlamp or flashlight, and part hair (particularly on the periphery of hair patches). Chewing lice are light brown with a rounded head and will move away rapidly. Sucking lice have pointed heads and are grey or blue in colour and often stay attached in place. It is also important to check some animals that are not showing signs, as these animals can also be harbouring lice without displaying symptoms.

The life cycles of both types of lice are regulated by temperatures. Lice increase as temperatures cool and populations peak during the late winter months. This often coincides with when producers confine cattle to smaller areas, which enables lice to spread quickly from animal-to-animal as well as from cow-to-calf. A management priority may be for producers to have their cow herd lice-free prior to calving season to avoid transmitting parasites to young calves. Adult lice often fall off as animals shed their winter hair coats. Warmer weather and longer days lead to a drop off in lice populations, and lice issues are uncommon during hot summer months.

Some cattle are chronic carriers of lice and should be culled. Lice can be managed through control and prevention strategies as well as chemical controls such as pour-ons, dusts or sprays. Note that different active ingredients may have different results. For example, pyretheroid products work on all types of lice but macrocylic lactones (i.e. ivermectin) are most effective on sucking lice.

Isolate and inspect new animals and treat them for lice ten to fourteen days prior to allowing them to join the rest of the cattle to prevent infesting the main herd. This may mean quarantining new entrants. When combining herds, it’s important that all animals have been treated for parasites within a four-week window otherwise untreated animals will infest the others. Remember to treat bulls. Avoid treating animals too early in the fall when temperatures are still warm and lice are not a problem.

Chorioptic Mites

Chorioptic mites (Chorioptes bovis) can cause livestock visible irritation, particularly in late winter. These mites are very small and can only be diagnosed from skin scraping using a microscope. Cattle that are affected with these mites exhibit “mange” which is the host animals’ allergic response to the mites’ saliva. Signs of mange include scabs, lesions, or mats of hair along the tail, udder, or down the back legs.

As with lice, chorioptic mites can transfer between animals, especially during winter confinement. The mites can also survive in bedding for a brief time. Similar prevention and control strategies that target lice will help to prevent mite infestations, including isolating new entrants to the herd.

Flies

There are two main types of fly pests that target livestock: blood-feeding flies (i.e. mosquitoes, horn, horse and deer flies, black flies, biting midges), and dung-inhabiting flies (i.e. stable, house and face flies).

Horn Flies

The horn fly is one of the most economically damaging species for cattle producers. Horn flies require fresh, undisturbed manure from grass-fed cattle to complete their life cycles. When bothered by horn flies, cattle will appear irritated, expend a lot of energy trying to avoid the flies, and exhibit other changes in animal behaviour, such as grazing activity.

Flies can be challenging to identify; however, horn flies have some unique characteristics that help producers identify them. Horn flies are charcoal grey in colour, approximately 5 mm in length, and their wings remain partially open in a V-shape when they are at rest. Horn flies tend to stay on animals for long periods of time, clustering on the head, shoulders, and back.

The economic threshold for control of horn flies in beef cattle is 200-300 flies per animal. Effective control of horn flies can be achieved by disrupting the pest’s life cycle through disturbing their preferred habitat of fresh manure. Grazing practices, such as high-intensity, low-frequency grazing may disrupt and break up manure patties, potentially reducing horn fly populations. Maintaining active dung insect populations, which effectively break down manure pats, can also be an effective method of reducing horn fly habitat. There are also a variety of chemical control options such as sprays, oilers, ear tags, or pour-ons. Some of these insecticides are passed through the animal, impacting parasite growth in the dung.

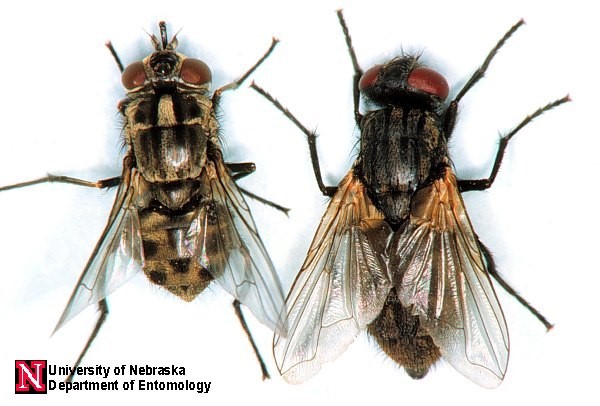

Stable Flies and House Flies

Stable and house fly pests develop in similar environments, and mainly thrive in confined production environments. These pest species develop well in manure (particularly from cattle on concentrated feeds), decaying crop residue, and spoiled feed.

When comparing house flies to stable flies, house flies are slightly larger and have cream-coloured abdomens whereas stable flies are smaller, have black spots on their abdomens, as well as a painful, irritating bite. While house flies are a nuisance, stable flies have more serious consequences, causing cattle irritation, triggering cattle to bunch up, reducing feed conversion, and lowering gains. Stable flies congregate on an animal’s legs and the economic threshold for treatment is 3-5 flies per front leg, or 25 flies per animal.

Prevention is a key control option for stable and house flies. Sanitation is important to destroy or reduce sites where pests develop. Stable and house flies prefer damp, wet conditions, so implementing adequate drainage practices helps, as does regular manure removal and eliminating piles of spoiled feed or silage. Fly traps may work. Several biological controls are available but are best used in conjunction with other cultural or physical control options. For pest management on a small scale, producers can buy and release parasitoid wasps which will feed on the developing flies. Ducks and chickens can reduce the parasite burden by feeding on flies, too. Chemical sprays have limited use on stable flies because they quickly rub the product off. Residual wall sprays are effective for controlling house and stable flies as these species rest on vertical structures.

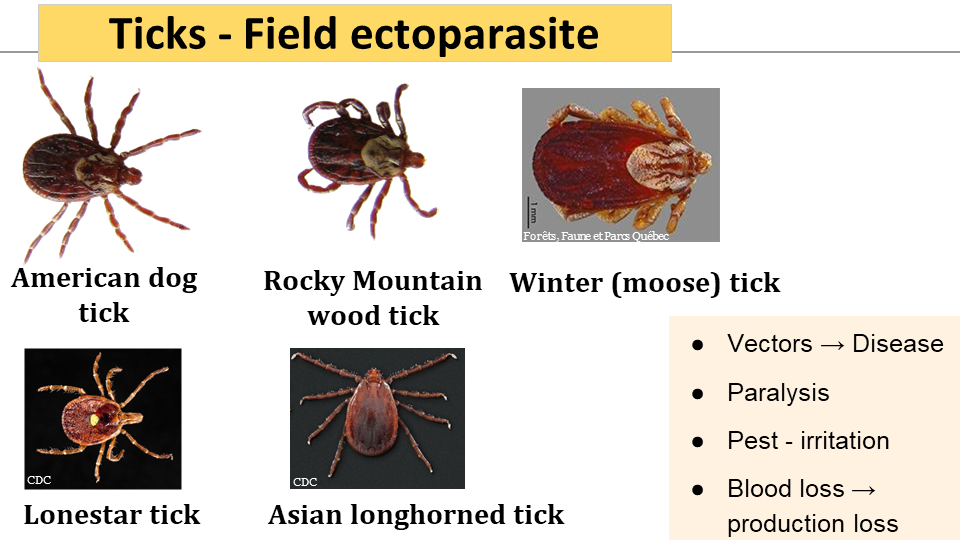

Ticks

Cattle grazing range and pastureland may be affected by ticks. In Canada, there are three main tick species that can infest cattle including the American dog tick, Rocky Mountain wood tick, and moose (winter) tick. These tick species are also all vectors for human diseases transmission such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Ticks can also carry and transmit livestock diseases, such as bovine anaplasmosis, from one animal to another. Some populations of the Rocky Mountain tick can also cause paralysis in cattle in parts of British Columbia due to a neurotoxin released through the tick’s mouthparts.

Experts are also monitoring two types of ticks, the Asian longhorned tick and the lonestar tick, which are spreading northward in the northeastern United States. Both of these tick species could have tangible impacts on beef cattle directly or through human disease transmission if they become established in Canada.

In general, ticks can cause blood loss, irritation, and production loss. Control measures through cultural or physical means is primarily geared toward keeping ticks away from animals, or keeping animals away from known tick reservoirs in pastures. Managing vegetation to reduce tick habitat or keeping cattle out of a certain pasture for a while may also help reduce tick infestations. There are no biological controls that are effective on a large scale, although a fungal pathogen is being studied as a potential control method. Chemical control is the main method of tick control and includes sprays, pour-ons, or products distributed through cattle oilers that list ticks on the control label. Broad-scale environmental application of insecticides is not recommended due to environmental contamination and non-target impacts on other species.

Anaplasmosis

Anaplasmosis (sometimes refereed to as ‘yellow bag’ or ‘yellow fever’) is a blood borne, infectious disease that is usually spread through tick bites but can be spread through other methods where animals are directly inoculated with contaminated blood (eg. Blood contaminated surgical tools, needles, dehorning equipment etc.). Anaplasmosis is cased by a microscopic parasite Anaplasma marginale that lives in the red blood cells of infected animals.

There are 4 stages of Bovine Anaplasmosis:

- Incubation stage: this stage lasts from the moment the animal is infected with the parasite until approximately 1% of their red blood cells have been infected (3-8 weeks). The animal will not show any signs of the disease during this stage.

- Developmental phase: signs of the disease begin to appear as the animal’s body attempts to destroy the parasite. This stage only lasts from 4-9 days. This is the most critical stage of infection as the animal will either improve or die within a few days of showing clinical signs.

- Convalescent stage: the animal’s body is slowly beginning to recover as red blood cell production increases. This stage of the disease can last from 2-3 months. Long term signs such as weight loss, abortion and secondary infection will show up.

- Carrier stage: at this stage animals are no longer showing signs of infection but their blood is still infected. This means that they can still pass the disease on to other animals. Infected animals will remain a carrier for the rest of their lives. Carrier cattle usually don’t show signs of the disease but may relapse if they are immunosuppressed due to a different disease.

Signs

Signs of anaplasmosis vary greatly depending on the age of the infected animal. Generally, the older the animal is the more severe the infection is. Cattle less than 6 months tend to show very few signs of infection. In contrast, up to 30-50% of mature cattle (over 3 years old) will die. Due to the rapid progression of the disease, dead cattle are often the first sign of the disease.

Other signs include:

- Fever

- Anaemia (pale gums)

- Jaundice (yellow gums)

- Weakness, reluctant to move

- Respiratory distress (easily become short of breath)

- Depression

- Decreased feed intake

- Recumbency (reluctant to get up)

- Abortions

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is often done on farm by presence of clinical signs, and confirmed via laboratory testing of blood samples. Talk to your veterinarian if you suspect your herd is infected with anaplasmosis.

Treatment

Treatment options are very limited once clinical signs have been observed. Antibiotics do very little to help stop the progression of the disease but long-acting tetracycline can be given to help prevent death if the desease is caught early. If the disease has advanced too far, the excitement of moving the animal through a handling facility to administer treatment may cause the animal to die of anoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain caused by a reduced number of red blood cells to transport oxygen). Consult a veterinarian before administering treatment.

Prevention

There is no vaccine approved in Canada for treatment of anaplasmosis. The only methods of prevention involve preventing the animal from being inoculated with contaminated blood. Some of these methods include

- Cleaning and sanitising surgical tools between uses

- Not reusing needles on different animals

- Proper disposal of contaminated needles

- Controlling ticks and horse flies (especially during later summer months when most active)

- Culling infected animals

Reporting

Anaplasmosis is an immediately reportable disease in Canada, meaning that laboratories are required to report suspicion or diagnosis of the disease to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

Responsible Use of Insecticides for Beef Cattle

It is important to use chemical management strategies wisely to minimize resistance and maintain effective parasite control. Management practices producers can employ include:

- Avoid unnecessary treatments: treat only if parasites are present;

- Follow label directions and apply the correct product for the correct target species at the appropriate time and at the proper dosage;

- Discuss pesticide selection and use with your veterinarian;

- Avoid back-to-back use of insecticides that have the same active ingredient;

- When possible, switch between modes of action (i.e. use a group 1B product one year and a group 3 product the next);

- Avoid applying spray- or pour-on products at temperatures lower than -10oC because the product can freeze and be less effective;

- Avoid treating animals when the number of parasites is low and not causing a problem;

- Avoid treating animals “just in case”;

- Adjust insecticide dosage (based on weight) for the animal being treated;

- Avoid applying product to wet animals;

- Keep good production records so you can quickly review which products were used in the past;

- If using fly control ear tags, avoid tagging prior to the onset of the fly season to prevent releasing insecticides into the environment when they won’t be effective for the target pest;

- Monitor pest populations following treatment to assess effectiveness.

Table 1: Common Parasite Control Products for Beef Cattle in Canada

| Common Parasite Control Products | Parasites Controlled | Mode of Administration | Examples of Brand Name of Products Registered for use in Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Parasites | |||

| Carbaryl | Horn flies, lice, winter ticks | Body spray | Sevin |

| Cyfluthrin | Horn flies, lice | Topical pour-on | CyLence |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin | Face flies, horn flies, Rocky Mountain wood ticks | Ear-tag (flies), pour-on (ticks) | Saber |

| Permethrin | Horn flies, lice, Rocky Mountain wood ticks | Topical pour-on | Boss |

| Pyrethrin | Horn flies, house flies, stable flies, mosquitos | Body spray | Numerous |

| Pyrethroid | Lice, horn flies, stable flies, black flies, house flies, horse flies, deer flies, ticks | Topical pour-on | Clean-Up II |

| Internal and External Parasites | |||

| Doramectin2,3 | Internal roundworms, lungworms, eye worms, cattle grubs, lice and mites | Topical pour-on, injectable | Dectomax |

| Eprinomectin2,3 | Internal round worms, lungworms, grubs, lice and mites | Injectable (sub-cutaneous slow-release formulation) Pour-on |

LongRange, Eprinex |

| Ivermectin2,3 | Internal roundworms, lungworms, cattle grubs, lice and mites | Topical pour-on, injectable | Bimectin, Ivomec, Noromectin |

| Internal Parasites | |||

| Albendazole1 | Internal roundworms, tape worms, lung worms | Oral drench | Valbazen |

| Fenbendazole1 | Internal Roundworms | Feed, Mineral, pellets Oral Drench |

Safeguard

Safeguard, Pancur |

| Decoquinate | Internal Coccidia | Feed | Deccox |

| Lasalocid | Internal Coccidia | Feed | Bovatec, Avatec |

| Monensin | Internal Coccidia | Feed | Rumensin, Coban, Monensin |

| Toltrazuril | Internal Coccidia | Oral drench | Baycox |

*Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information above. However, it remains the responsibility of the readers to familiarize themselves with the product information contained on the Canada product label or package insert. Ensure label directions and veterinarian instructions are followed when using any veterinary product.

1 Fenbendazole and albendazole belong to the same drug class (Benzimidazoles).

2 Ivermectin, Doramectin, Eprinomectin belong to the same drug class (Macrocyclic lactones).

3 Repeated use of products from the same drug class increases the risk that parasites will become resistant and the product will become less effective.

External parasite products were assembled from Recommendations for the Control of Arthropod Pests of Livestock, Poultry and Farm Buildings in Western Canada (Philip, H. 2017).

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at [email protected].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Kateryn Rochon from the University of Manitoba and Dr. Shaun Dergousoff from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada for contributing their time and expertise in writing and reviewing this page.

This content was last reviewed January 2024.