Contact your veterinarian if you observe or suspect an unusually high rate of mortalities or unusual or suspicious signs of death. Some diseases are federally reportable and need to be handled and disposed of extremely carefully.

Proper disposal of dead cattle helps control the spread of disease and prevent contamination of air, soil and ground water. On-farm mortality disposal is under provincial regulation.

Regulations differ across provinces, so check local regulations before adopting a particular method. Be aware that legality of disposal may also be subject to interpretation by local authorities who may restrict the use of a particular method if too many complaints are received.

Alternatives for disposal of cattle mortalities, along with their pros and cons, are listed below.

| Key Points |

|---|

| Deadstock pickup (for rendering, anaerobic digestion, thermal hydrolysis or incineration) provides excellent disease control but can be costly for producers. |

| Composting is a natural process in which bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms break down deadstock and other organic material into compost. Composting requires water and nutrients (typically provided by manure) and air (provided by periodic mixing). |

| Burial requires a pit at least 1 meter deep (and pre-planning, particularly in winter). Water contamination is a risk in poorly drained soils or soils with a high water table. Record burial sites. |

Introduction

Deadstock pickup

Removing dead stock from the farm (for rendering, incineration or thermal hydrolysis or anaerobic digestion) requires minimal effort and provides excellent on-farm disease control. Deadstock pickup costs have increased after the advent of BSE as only hide and tallow products can now be marketed, but the meat and bone meal cannot.

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| Excellent on-farm disease control | May be costly to producers – depends on distance to plant |

| No residues or other aftermath – less scavenging/predation | Minimum weights for pickup often required |

| Easy – just call for pick up | Dead stock pickup not available everywhere |

| Excessive time may elapse before pickup – may require proper storage |

Composting

Composting is a naturally occurring process in which bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms convert organic material into a stabilized product called compost. Composting of livestock mortalities involves two phases.

In the first phase, the animal carcasses are placed in a composting bin or on a windrow of straw. A bulking agent that is high in carbon, such as sawdust or straw, is added to completely surround the carcasses. This heap is entirely covered with manure, which is full of microbes. Anaerobic microorganisms (those not requiring oxygen) work in the carcass to degrade it.

Photo credit: Dr. Kim Stanford, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

The second phase involves regularly turning the pile and introducing air to feed aerobic microorganisms (those requiring oxygen), which degrade these materials produced by the first stage into odour-free carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). This stage causes the temperature of the compost pile to rise, which kills common viruses and other bacteria that may be present.

Science-based composting was first developed for the poultry industry, but research expanded its use to cattle mortalities in the Canadian climate after the advent of BSE. Composting requires some time and effort, although costs for raw materials are minimal. Disease control is good, and the resulting compost can be used as a fertilizer or soil amendment. The initial construction of the compost pile is key to the eventual success of the composting process. A bad set up (too wet, too dry, no carbon source) is not easy to remedy.

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| Inexpensive; uses materials available on farm | For intensive operations, there may not be sufficient land base |

| Good disease control | Would become more expensive if a covered building or specialized turning equipment was purchased |

| Can build compost as required year round | Compost requires management – monitoring temperatures and turning |

| Residual material used as fertilizer | More difficult in wet climates |

| Less scavenging/predation | Bones exposed at surface of pile do not degrade and may cause damage to manure spreading or crop harvesting equipment |

| Variable in length of time (2-6 months) for deadstock to decompose – advantage or disadvantage depending on scenario | Manure that was used to compost cattle carcasses cannot legally be removed for spreading on rented or neighbours’ land |

| Waste remains on farm – decreased biosecurity risk | Appropriate site and soil conditions required |

| Good option for mass mortality events |

Essentials of composting: Moisture

A target of 50 to 60% moisture in the initial build is optimal. The cattle themselves are a source of moisture, but manure and sawdust used in compost should be subjected to a “squeeze test”, if the dry matter content is not known. If it is possible to manually squeeze moisture from a sample, it is too wet. If the sample crumbles when squeezed, it is too dry. Optimal moisture is damp to the touch and forms a loose ball that would crumble if dropped to the ground. It is difficult to add moisture to a compost pile once it has been built. Small piles with one or two carcasses dry out more readily and have a greater risk of getting too wet due to rain or snow falls. Generally, compost piles should be shaped so that water does not pool on the compost, unless the climate is very dry.

Essentials of composting: Air

The growth of aerobic bacteria is essential for composting. If the compost becomes too wet, air flow is restricted, anaerobic bacteria flourish and the compost will have a foul stench. If compost is properly aerated and heating, no objectionable odors will be present, and predators will not scavenge from the compost piles.

If composting with manure, a manure-straw mix from a bedding pack makes an excellent compost amendment as the straw aids in compost aeration. If composting with sawdust, wood shavings or a larger particle size used in bedding are preferable to finer sawdust particles.

Source: Dr. Kim Stanford, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

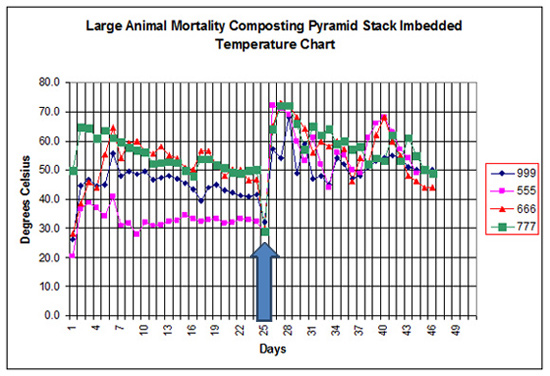

For cattle compost, turning 3 times at approximately 2-to-3-month intervals is generally sufficient to complete the composting process, provided the compost spent some weeks at 40 to 60oC.

Monitoring the temperature of the compost also provides guidance as to when compost should be turned. Commercial composting operations use specialized windrow turners, but a front-end loader is sufficient for smaller-scale composting. Drop the compost from the maximum height of the bucket to promote aeration and fracture the bones.

Fresh manure, sawdust or matured compost should be used to cover the surface of the pile after turning as bones exposed to sun do not degrade. Manure is a better substrate than sawdust for bone degradation.

Essentials of composting: Nutrients

Compost requires both carbon (C) and nitrogen (N). Ratios between 20:1 and 40:1 C:N are optimal. Straw and sawdust/shavings are excellent carbon sources. Manure contains lesser amounts of carbon, but the carbon and nitrogen in manure is readily available to compost microbes.

Laying cattle carcasses on a base of at least 18” (45 cm) straw or sawdust and heaping manure over the carcasses to a depth of at least 3.5’ (100 cm) will provide an appropriate C:N ratio. Soil cannot be used in place of manure due to a lack of nutrients. Turning the compost every 2-3-months is also necessary to re-distribute nutrients and ensure more uniform heating and degradation of the mortalities.

Other composting considerations

Photo credit: Dr. Kim Stanford, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

A windrow layout, with carcasses in a single line, is the easiest to manage. Carcasses should be placed at least 18” (45 cm) from the edge of the pile to ensure adequate coverage and nutrients. Carcasses should also be at least 10” (25 cm) apart to promote air flow.

Degradation of carcasses is impaired if they touch. Carcasses should be laid on their side as feet protruding from a carcass pile will not degrade. The windrow can be extended as new mortalities arrive and carcasses rapidly covered to prevent attracting scavengers to the pile.

Photo credit: Dr. Kim Stanford, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Winter composting is possible and piles can be started at temperatures of -20oC or colder, provided that either the carcasses or the stockpiled manure is warm. Compost using sawdust without manure may be more difficult to make under winter conditions.

Burial

Planning is required for disposal by burial. A pit is necessary for disposal of cattle and may be difficult to dig during winter months. In areas with a high water table, burial may not be allowed and offset distances between burial pits to ground and surface water sources are required. Sites prone to flooding or erosion are not suitable for burial pits.

Lime is frequently added to burial pits for odor control, but also limits microbial activity and slows degradation of buried carcasses. Cattle carcasses buried with lime during the Foot and Mouth disease outbreak of 1952 have been discovered relatively intact. Controlled access to the pit is necessary to prevent predation of mortalities and accidental entry of livestock and people into the pit.

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| Permanent containment for disease outbreaks | Need to have sites ready for winter burial |

| May be good choice on a large land base with suitable soil, topography and access to a backhoe | Ground water contamination possible and odor of an open pit is a magnet for predators |

| Cost-effective and relatively quick to develop | May be costly if multiple burial pits are required |

| Minimal management | Decomposition timeline highly variable |

| May require assessment for future land use |

Incineration

In Canada, incineration is currently used for disposal of cattle carcasses only at a limited number of research installations due to the expense and infrastructure required. Incineration requires extremely high temperatures ( > 800oC in chamber) and the appropriate equipment. This is the best option for disease control as carcasses are reduced to ash, with all infectious agents destroyed. The ash does require disposal and fuel costs for incineration of cattle are high. High temperature incineration should not be confused with burning. Burning is seldom legal and results in excessive air pollution and risks of disease transfer from carcass residues.

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| Superior disease control | Specialized and expensive equipment and fuel required |

| Mobile incinerators limit infrastructure costs | Time required may be impractical for multiple mortalities |

| Minimal air pollution/odors from high temperature incineration | Ash requires disposal |

| Less scavenging/predation | Extreme heat is on-farm hazard |

| Instant reduction in volume | |

| No temporary storage required |

Natural Disposal

Natural disposal involves offering cattle carcasses to the local predator/scavenger population. In jurisdictions where it is legal, this method is frequently used as deadstock pickup services have become more costly and less available. Little labor is required, but the risk of disease transfer is high. Cysticercosis, which requires a canine intermediate host is now present in some locales and leads to beef carcasses condemned at slaughter due to tape-worm cysts in muscles. Naturally, a well-fed predator population tends to multiply and increased calf predation has also been reported.

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| Easy and inexpensive | Not legal in all areas |

| Air, water and soil contamination | |

| Increased populations of predators and increased predation of cattle | |

| No disease control |

Anaerobic Digestor (Biodigestor)

Anaerobic digestion is a process where microorganisms break down compostable material such as food waste, without the presence of oxygen. Biodigestors can be an opportunity to capture greenhouse gas production and provide a renewable energy source from products such as manure and deadstock. Access and transportation of deadstock to a biodigestor facility may be limited depending on your location. Centralized biodigestors will require additional treatments of biodigestor products to eliminate infectious prions (BSE) before land-spreading, which will increase costs.

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| Reduce odour and pathogen levels in manure | Not accessible in every province, it is currently available in Lethbridge, AB |

| Reduce greenhouse gas production from a farmstead | Infrastructure is expensive |

| Produce renewable energy | Maintaining the “recipe” for biogas production due to the various types of wastes used |

| Utilize food by-products and other organic materials sourced off-farm | Has to be used along with a prion control technology which increases costs of centralized facilities. |

| Improve the fertilizer value of the manure |

Thermal Hydrolysis

Thermal Hydrolysis (THD) uses a combination of high temperature (356°F) and high pressure (174 psi) to break tissue down to very small parts. Like biodigesters, THD can be used to produce renewable energy such as biogas from animal by-products (including deadstock). It can also destroy the prions that cause bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE).

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| Complete pathogen destruction | Not accessible in every province, it is currently available in Lethbridge, AB |

| No groundwater contamination risk from disease | Infrastructure and energy required increases costs |

- References

-

Open-air windrows for winter disposal of frozen cattle mortalities: effects of ambient temperature and mortality layering. 2007. K. Stanford, V. Nelson, B. Sexton, T.A. McAllister, X. Hao and F. Larney. Compost Sci. Util. 15: 257-266

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at [email protected].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Kim Stanford, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry Beef Research Scientist for contributing her time and expertise to writing this page.

This content was last reviewed November 2023.