Bovine Respiratory Disease in Beef Cattle

Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD), sometimes described as “shipping fever,” is the most common and costly disease affecting the North American beef cattle industry. In the broadest sense, BRD refers to any disease of the upper or lower respiratory tracts.

Although commonly associated with the feedlot, BRD can also be a significant problem in cow-calf herds. Several BRD pathogens can also cause abortions in pregnant cows, and BRD is a leading cause of illness, antibiotic treatment and death in nursing calves between three weeks of age and weaning. BRD can be much more difficult to detect and effectively treat in cows and calves on pasture compared to cattle in confined facilities. Delayed BRD diagnosis and treatment increases the risk of secondary bacterial infections, severe illness and death.

Respiratory infections are the leading cause of antibiotic treatments in calves from birth to weaning. At least one calf was treated for respiratory disease on 77% of Western Canadian cow-calf operations.1

BRD accounts for 65-80% of the morbidity (sickness) and 45-75% of the mortality (deaths) in some feedlots.2

| Key Points |

|---|

| Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD) is the most common and costly disease affecting the North American beef cattle industry. |

| BRD is most prevalent within the first weeks of arrival to the feedlot, but can also occur later in the feeding period. |

| Classical clinical signs of bacterial BRD include:

– fever of over 40°C (>104°F), |

| Risk factors include:

– management factors such as poor vaccination, |

| Prevention in cow-calf operations:

– Ensure calves receive adequate, high-quality colostrum at birth |

| Prevention in feedlots:

– Purchasing directly from cow-calf operators minimizes unnecessary commingling and disease spread among weaned calves |

Causes

BRD is a complex disease involving several interacting factors. For example, researchers can recover many of the bacteria and viruses responsible for BRD from the nasal passages of healthy cattle. However, other factors such as the stresses from transportation, mixing unfamiliar cattle and adverse weather create the right mix of circumstances for BRD to develop. There are three main categories of factors associated with all diseases, and BRD in particular:

- Host factors, which refers to the characteristics of an animal that make it more prone to the disease, such as: age, nutritional status, immune status, prior exposure to the pathogens, genetics (e.g., crossbreds generally have better health performance than straightbred cattle)

- Infectious agents or pathogens must be present to cause the disease. These can broadly be categorized as viruses, bacteria and parasites:

- Viruses, including bovine herpes virus (which causes infectious bovine rhinotracheitis or IBR), bovine parainfluenza virus (PI-3), bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVD) and bovine coronavirus (BCV). These viruses usually cause the initial BRD infection and predispose the animal to subsequent bacterial BRD infections. Several of these viruses can also cause significant reproductive (BVD, IBR) or diarrhea (BVD, BCV) challenges in cow-calf operations.

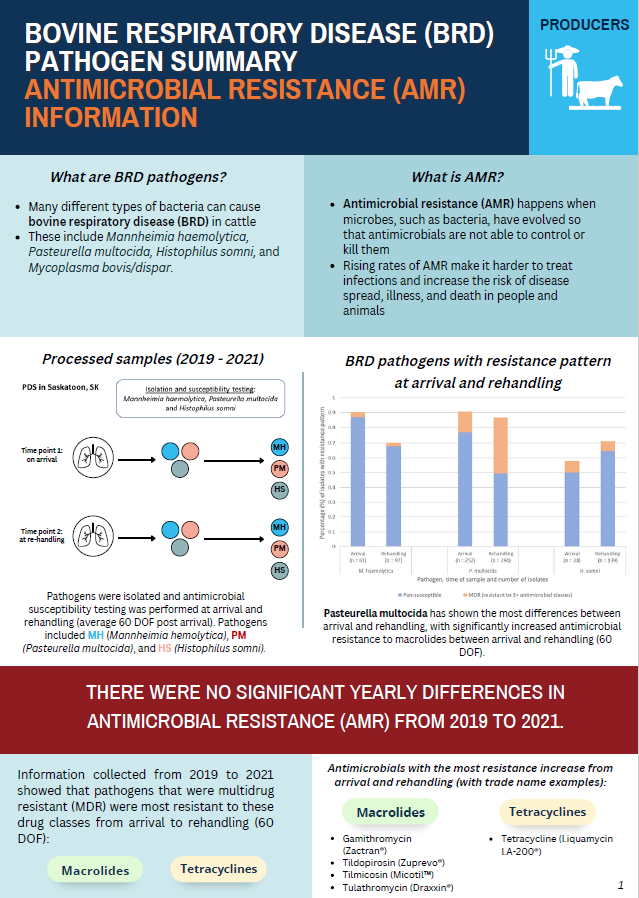

- Bacteria, including Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, Histophilus somni and Mycoplasma bovis.

- Parasites, including lungworm.

- The environment that the animal is in may increase the risk factors for disease. Animals in overcrowded conditions, in poor air quality (poor ventilation, dust, smoke), sourced from auction markets or stressed by transport, commingling, temperature fluctuations, etc. are more likely to develop the disease

Video: Recognizing Respiratory Distress in Cattle

This interview with veterinarian Dr. Steve Hendrick, DVM, by RealAgriculture.com explains how to recognize and deal with cattle with respiratory disease.

The next video begins with an excellent explanation of BRD. It is included for information purposes only and does not constitute or imply an endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the BCRC or the CCA.

Clinical Signs

The viruses that cause IBR and BVD can cause abortion in unvaccinated females. The BVD virus can suppress immunity and lead to a variety of infectious diseases in young calves.

BRD pathogens cause respiratory disease in calves prior to weaning. Clinical signs of BRD in pre-weaned calves, feedlot calves and grass cattle include:

- fever of over 40°C (>104°F)

- difficulty breathing occurred to varying degrees

- nasal discharge

- varying degrees of depression

- diminished or no appetite (“off feed”)

- rapid, shallow breathing

- coughing

BRD is the most common disease of feedlot cattle, with peak incidence (often associated with Mannheimia haemolytica) generally occurring within two weeks of arrival. Generally, cattle exhibiting signs of depression separate themselves from the rest of the herd, and diligent pen checkers will usually identify most sick animals. Body temperature is commonly used to determine whether cattle should be treated. Body temperature is such an important diagnostic test that many feedlots will treat animals based upon an undifferentiated fever (UF).

BRD can also occur 30-40 days after arrival, after the stock attendants have reduced their level of surveillance of newly arrived animals. These BRD cases are more likely to involve Mycoplasma bovis, and their clinical signs can be more difficult to detect. Cattle with Mycoplasma pneumonia may not appear depressed, but instead demonstrate a chronic cough and weight loss. Mycoplasma can also infect joints and result in a profound lameness, reluctance to move, poor appetite and a poor or prolonged response to treatment.

Risk factors

BRD is considered a polymicrobial disease, which means that it arises from infections with a combination of bacteria and viruses. In addition, several other factors influence the susceptibility of an animal to developing BRD. Any one risk factor alone may not trigger BRD, but several risk factors together form an additive effect that can predispose the animal to BRD.

Management factors have been associated with BRD for decades. Regardless of herd size, outbreaks of BRD (20% of herds) were most common in herds that had purchased 10 or more bulls, used community pastures, bought cows or did not vaccinate newly purchased animals.3 Historically, feeder cattle were often shipped by train, particularly to large markets in the United States. It was recognized at the time that shipping was a risk factor for BRD, and hence pneumonia in cattle was termed “shipping fever.” A study involving calves arriving at 21 U.S. commercial feedlots from 1997 to 2009 concluded that distance traveled was correlated to the incidence of BRD.4 This, however, has not been substantiated in Canada.

Weather has always been implicated in the occurrence of BRD, presumably because the greatest incidence of BRD occurs during the fall. However, this is confounded by the fact that it is also when the greatest number of calves is being assembled, mixed (commingled) and transported. A study involving 288,388 head of cattle, arriving at nine U.S. commercial feedlots during September to November in 2005 to 2007, found that wind chill and temperature change were associated with an increased incidence of BRD.5

Some studies have found a higher incidence of BRD in auction market versus ranch-derived calves. Furthermore, the incidence of BRD increases with the level of commingling; calves assembled from multiple lots are more likely to have BRD than pens composed of larger groups of calves from fewer sources. There is also considerable anecdotal evidence that the quality of the calves purchased is highly associated with the incidence of BRD, with poorer quality calves (e.g., lightweight, malnourished, uncastrated, unvaccinated) having more BRD. Studies also conclude that lighter weight calves have a higher risk of developing BRD than do their heavier pen mates.

It is unclear whether heifers are more prone to developing BRD than steers. A large-scale U.S. study involving 21 million animals found that heifers were at a greater risk of developing BRD than were males from 1997-1999, but no difference in between steers and heifers was found during 1994-1996.6

Rapid introduction to high-grain rations may also precipitate cases of BRD.

The risk factors associated with an outbreak in one feedlot may not be the same as outbreaks at other feedlots involving similar types of animals in similar conditions.

Prevention

Disease prevention in the cow-calf herd

Vaccination: Work with your veterinarian to develop and implement a prevention-based herd health management program for both the breeding herd and calf crop. Follow the label and veterinary instructions and ensure the initial (priming) vaccination is followed by the booster vaccination to ensure optimal immune protection. Your veterinarian will be able to recommend a vaccination program that is appropriate for your herd, your management system and your marketing practices.

Producers can use the Cost-Benefit of Feeding BRD Vaccinated Calves tool to calculate the costs, risks, and economic benefits of feeding calves that have been vaccinated for BRD compared to calves that have not.

Biosecurity: Your veterinarian can also help you develop an effective biosecurity program to reduce the risk that new diseases will be introduced when new bulls or replacement females are introduced to the herd.

Colostrum: The first few hours of the calf’s life are critical to determining whether it survives to weaning and beyond. Without colostrum, the newborn calf’s immature immune system can’t adequately protect it against diseases like scours. But enough colostrum of adequate quality will give the calf a good start in life that pays health dividends through weaning.

Nutrition: Test your feed and work with a nutritionist to balance the ration and correct any deficiencies or imbalances. Good feed supports good health, and good overall health is key to combatting BRD pathogens. Cows in good body condition score (BCS) also produce more and higher-quality colostrum.

Stress: Stress depresses the immune system, makes it harder for the animal to fight off pathogens or take full advantage of protective vaccines. It’s impossible to eliminate stress, but castrating, dehorning, branding (if necessary) and vaccinating early in life takes some of the stress off at weaning/processing time in the fall, which is a stressful time already. Low-stress weaning practices (e.g. two-stage, fenceline weaning) can improve feed intake and reduce the need for BRD treatments.

Crowding: Cattle are more likely to transmit BRD pathogens when they are in close contact. Transportation, regular handling and sorting (e.g., during processing) and intensive grazing practices may increase the risk of disease spread.7

The health benefits of these practices are not restricted to BRD. They help reduce the risk of most, if not all diseases caused by viruses, bacteria or parasites.

Preconditioning appears to have some benefit in preventing BRD, with weaning four to six weeks before sale being the most important component of a preconditioning program. The concept of preconditioning calves to decrease stress levels was first introduced in 1967. While there is considerable variation in what constitutes a preconditioning program, the central components entail:

There appears to be agreement that weaning and/or vaccinating at least three weeks prior to shipping is beneficial.

- vaccination for respiratory viruses and bacteria

- vaccination for clostridial bacteria

- weaning 30 to 45 days in advance of a sale

- dehorn and castrate as early in life as practical to reduce growth setbacks and additional stress near weaning

- train calves to feed from a bunk

Some feedlots prefer to “place” calves in winter (January, February) recognizing such groups of calves have very likely been weaned and “bunk broke” prior to arrival and are past the period of highest BRD risk.

After calves arrive at the feedlot

Vaccines for respiratory diseases are routinely administered upon arrival at the feedlot, which may also be a difficult time for a stressed calf to mount an effective immune response. A recent review of the scientific literature found no clear benefit from vaccinating calves upon arrival at the feedlot.8 Another review relating to Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somnivaccines concluded that there was a potential benefit for vaccinating feedlot cattle against M. haemolytica and P. multocida but not H. somni.9

Nutrition may affect incidence of BRD. One review found that increased energy density (concentrates) will improve ADG without adversely affecting the incidence of BRD.10 Other studies found that the incidence of BRD tended to increase once concentrates exceeded 50% of the diet.11 Similarly, BRD morbidity increased once crude protein exceeded 14%. There is not enough evidence to conclude that injected doses of vitamins A, D and E will reduce BRD. A wide range of studies have also examined supplementing with potassium, thiamine, B-vitamins, copper, zinc, vitamin E, selenium and bypass protein. Although these studies haven’t shown that supplementing with these nutrients significantly reduce the incidence of BRD, it’s likely that significant deficiencies of these nutrients would almost certainly impair animal health.

Metaphylactic treatment strategies using injectable antibiotics can help control BRD in high-risk calves, and likely are more effective than oral antibiotics since stressed cattle may not be eating or drinking regularly.12 It is important that producers consult with their veterinarian regarding the use of antibiotics for the control and treatment of BRD, especially in terms of avoiding antibiotic resistance.

Good animal husbandry can also help reduce the risk of disease. Providing clean, dry bedding, protection from prevailing winds, avoiding overcrowding, using low-stress handling techniques, proper ventilation of barns and minimizing dust can help to reduce disease.

Treatment

There is a large body of scientific knowledge regarding the beneficial effects of antibiotics for treating BRD. The question is not whether to treat an animal diagnosed with BRD with an antibiotic, but rather, “which antimicrobial works best?” There is no simple answer to this latter question, but your veterinarian is a good place to start.

Ancillary drugs, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS) and immunomodulators, have been used to treat BRD for decades. However, many of the studies have been small-scale experiments and there is a lack of data from well-designed, large-scale, clinical trials. However, a 2011 study found that meloxicam (NSAID) administered in water 24 hours before castration at the feedlot significantly reduced the number of animals that developed BRD.14

Even when working with the best recommendations, sometimes treatments fail. Common causes of treatment failure include:

- Disease too far advanced (due to delayed detection and treatment)

- Wrong diagnosis (e.g., calves are sick with a nutritional disease like grain overload)

- Viral infections with no bacterial involvement

- Simultaneous disease process (e.g., overt IBR in feedlot calves, post-calving metritis in cows)

- Inappropriate antibiotic used (i.e., the organism is resistant to the antibiotic chosen)

- Overuse or inappropriate use of ancillary drugs like anti-inflammatory and immunomodulator drugs

Doing necropsies on sick animals early in an outbreak can help to diagnose and treat the problem more quickly and accurately, potentially allowing time to develop protocols to deal with the disease more appropriately.

Carcass Quality Considerations

Current Research

Research into BRD is happening on numerous fronts. Current research is looking at further understanding the respiratory microbiome and the differences in the microbiome between healthy and sick cattle. Current research is also examining antibiotic resistance, improved diagnostics, more reliable and effective non-antibiotic therapies, better vaccines and a more solid understanding of the disease complexes.

- References

-

1. Waldner CL, Parker S, Gow S, Wilson DJ, Campbell JR. Antimicrobial usage in western Canadian cow-calf herds. Can Vet J. 2019 Mar;60(3):255-267. Available here.

2. Smith RA. Impact of disease on feedlot performance: a review. J Anim Sci. 1998;76:272-274. Available here.

3. Wennekamp TR, Waldner CL, Parker S, Windeyer MC, Larson K, Campbell JR. Biosecurity practices in western Canadian cow-calf herds and their association with animal health. Can. Vet. J. 2021 Jul;62(7):712-718. Available here.

4. Cernicchiaro N, White BJ, Renter DG, Babcock AH, Kelly L, Slattery R. Associations between the distance traveled from sale barns to commercial feedlots in the United States and overall performance, risk of respiratory disease and cumulative mortality in feeder cattle during 1997 to 2009. J Anim Sci. 2012 Jun;90(6):1929-39. Available here.

5. Cernicchiaro N, Renter DG, White BJ, Babcock AH, Fox JT. Associations between weather conditions during the first 45 days after feedlot arrival and daily respiratory disease risks in autumn-placed feeder cattle in the United States. J Anim Sci. 2012 Apr;90(4):1328-37. Available here.

6. Loneragan GH, Dargatz DA, Morley PS, Smith MA. Trends in mortality ratios among cattle in US feedlots. J Am Vet Mad Assoc. 2001 Oct;219(8):1122-7. Available here.

7. Woolums AR, Berghaus RD, Smith DR, Daly RF, Stokka GL, White BJ, Avra T, Daniel AT, Jenerette M. Case-control study to determine herd-level risk factors for bovine respiratory disease in nursing beef calves on cow-calf operations. JAVMA. 2018 Apr;252(8):989-994. Available here.

8. Francoz D, Buczinski S, Apley M. Evidence related to the use of ancillary drugs in bovine respiratory disease (anti-inflammatory and others): are they justified or not? Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2012 Mar;28(1):23-38. Available here.

9. Larson RL, Step DL. Evidence-based effectiveness of vaccination against Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somni in feedlot cattle for mitigating the incidence and effect of bovine respiratory disease complex. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2012 Mar;28(1):97-106. Available here.

10. Taylor JD, Fulton RW, Lehenbauer TW, Step DL, Confer AW. The epidemiology of bovine respiratory disease: what is the evidence for preventive measures? Can Vet J. 2010 Dec;51(12):1351-9. Available here.

11. Galyean ML, Perino LJ, Duff GC. Interaction of cattle health/immunity and nutrition. J Anim Sci. 1999 May;77(5):1120-34. Available here.

12. Van Donkersgoed, J. Meta-analysis of field trials of antimicrobial mass medication for prophylaxis of bovine respiratory disease in feedlot cattle. Available here. Can Vet J. 1992 33:786-795. Available here.

13. Coetzee JF, Edwards LN, Mosher RA, Bello NM, O’Connor AM, Wang B, KuKanich B, Blasi DA. Effect of oral meloxicam on health and performance of beef steers relative to bulls castrated on arrival at the feedlot. J Anim Sci. 2012 Mar;90(3):1026-39. Available here.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at [email protected].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to:

- Dr. John Campbell, Professor, Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences, University of Saskatchewan

- Dr. Murray Jelinski, Professor and Alberta Chair in Beef Cattle Health and Production Medicine at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan

for contributing their time and expertise to writing this page.

This content was last reviewed September 2024.